|

British

Columbia Passenger License Plates

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quick Links: |

The period between 1931 and 1977 is considered to be the "Prison Era" when BC plates were manufactured by inmates at Oakalla Prison in Burnaby. |

*

* * * * |

| 1973-78 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

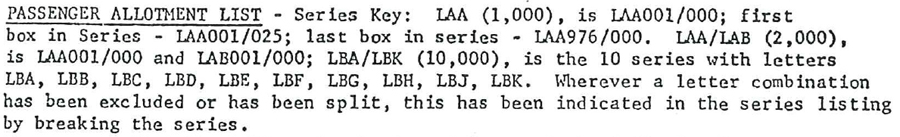

What was changing was the material that the plates would be made from, with a switch from metal (which rusted) to a new “heavy aluminum” that would only be replaced “when necessary.” It was estimated that these plates could last for 7-10 years, which happened to coincide with what many manufacturers considered to be the average life span of a car built in the early 1970s. As will be recalled, the (then) Attorney-General, Lesley Peterson, had announced this series back in the late-1960s and said it would be used for a period of five years. The Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) was also addressing the trailer hitch problem with the 1970 plates by moving the decal box to the top-right corner of the license plates. As it was a new license plate base, no registration decals would be issued for 1973, but would be for 1974 and every year afterwards. Finally, whereas the 1970 license plate series had started at AAA-001, the 1973 series would start at LAA-001 and would ultimately progress as follows (see also the Galleries below):

|

Whereas the province had distributed the various letter prefixes used on the 1970 base by geographic region in the hopes of aiding the tourism industry (e.g. “A” & “B” on Vancouver Island, “K” for the Okanagan and Kootenay's, etc.), this was not done with the 1973 base. While the Distribution List used by the MVB does exist for the 1973 base and includes locations where blocks of plates were sent, this no rhyme-nor-reason to the distribution (as can be seen in the Galleries below), either by geographic region or the urban hierarchy that had been used with the 1952 license plates. Rather, the only motivating factor appears to have been a desire to ensure the first plates in the series were not provided to the Menzies Street office in Victoria in order to avoid the fiasco of who should have been issued the first plates (AAA-001 and AAA-002) in the 1970 series. To help explain the initial distribution of the 1973 plates, the Motor Vehicle Branch included a “Series Key” with the “Allotment List” provided to its various field offices. Of note, this is the last time that such a list would be used as plates would, henceforward, be distributed to offices on an “as needed” basis through the year. |

| Gallery - "L" Bloc | ||||

LAF ("Excluded") |

LAG / LBG (Abbotsford - 11,000) |

LBH / LDF (Chilliwack - 19,000) |

LDG / LEC (Dawson Creek - 7,000) |

|

LED / LFG (Haney - 14,000) |

LFH / LHJ (Kamloops - 22,000) |

LHK / LJD (Mission - 5,000) |

LJE / LKK (New Westminster - 16,000) |

|

| Gallery - "M" Bloc | ||||

MAA / MDK (New Westminster - 40,000) |

MEA ("Excluded") |

MEB / MED (New Westminster - 3,000) |

MEE ("Excluded") |

|

MHG / MKK (Richmond - 24,000) |

||||

| Gallery - "N" Bloc | ||||

NAA / NAF (Richmond - 6,000) |

NAG ("Excluded") |

NAH / NAK (Richmond - 3,000) |

NBA / NBB (Richmond - 2,000) |

|

| Gallery - "P" Bloc | ||||

PEA ("Excluded") |

PEB / PED (Vancouver, Georgia St. - 3,000) |

PEE ("Excluded") |

PEF / PEJ (Vancouver, Georgia St. - 4,000) |

|

PEK ("Excluded") |

PFA / PKK (Vancouver, Georgia St. - 50,000) |

|||

| Gallery - "R" Bloc | ||||

RAA / RAF (Alberni - 6,000) |

RAG ("Excluded") |

RAH / RBC (Alberni - 6,000) |

RBD / RBE (Ashcroft - 2,000) |

RBF / REC (Cloverdale - 28,000) |

RED ("Excluded") |

REE / REJ (Cloverdale - 5,000) |

RGH / RHG (Cranbrook - 10,000) |

||

RKB / RKE (Fernie - 4,000) |

RKF / RKK (Quesnel - 5,000) |

|||

| Gallery - "S" Bloc | ||||

SAA / SAB (Fort St. John - 2,000) |

SAC ("Excluded") |

SAD ("Excluded") |

SAE / SAF (Fort St. John - 2,000) |

SAG ("Excluded") |

SAH / SAJ (Fort St. John - 2,000) |

SAK ("Excluded") |

SBA / SBC (Golden - 3,000) |

||

SDJ (Lillooet - 1,000) |

SDK / SGB (Nanaimo - 23,000) |

SGC / SHF (Nelson - 14,000) |

SHG / SKK (North Vancouver - 24,000) |

|

| Gallery - "T" Bloc | ||||

TAA / TCA (North Vancouver - 21,000) |

TCB / TDE (Penticton - 14,000) |

TFJ / TGE (Prince Rupert - 7,000) |

TGF / TGH (Revelstoke - 3,000) |

|

TGJ / THB (Smithers - 4,000) |

THC / THG (Terrace - 5,000) |

THH / TJF (Trail - 9,000) |

TJG / TKK (Vernon - 14,000) |

|

| Gallery - "V" Bloc | ||||

VAA / VKK (Victoria - 100,000) |

||||

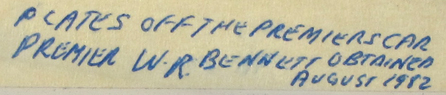

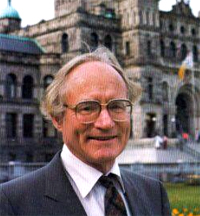

| William (Bill) Richards Bennett was the 27th Premier of British Columbia between 1975 and 1986. The No. VAB-002 plate was found in the collection of the late Len Garrison and included a note taped to the back indicating that the plate had been obtained in August of 1982 and had belonged to Bennett. |

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to verify the story but, as outlined above, the VAB bloc of plates had been issued to Victoria motorists in 1973, so, if correct, it is assumed this plate was attached to the car that Bennett used while in Victoria (the provincial capital). |

| Gallery - "W" Bloc | ||||

WAA / WAC (Vanderhoof - 3,000) |

WAD ("Excluded") |

WAE / WAF (Williams Lake - 2,000) |

WAG ("Excluded") |

WAH / WBB (Williams Lake - 5,000) |

WBC / WBF-500 (Creston - 3,500) |

WBF-501 / WBG (Fort Nelson - 1,500) |

WBH-001 / WBH-500 (Kaslo - 500) |

WBH-501 / WCA (Kitimat - 4,500) |

WCB ("Excluded") |

WCC / WCE-500 (Merritt - 2,500) |

WCJ-001 / WCJ-500 (Pouce Coupe- 500) |

WCJ-501 / WDE (Powell River - 6,500) |

WDF / WDG-600 (Burns Lake - 1,600) |

|

WDG-601 / WDH (Princeton - 1,400) |

WDJ / WDK-700 (Invermere - 1,700) |

WDK-701 / WEA (Rossland - 1,300) |

WEB-001 / WEB-600 (Clinton- 600) |

WEB-601 / WEC (Salmon Arm - 1,400) |

WED ("Excluded") |

WEE / WEH (Salmon Arm - 4,000) |

WEJ / WEK-500 (Ganges - 1,500) |

WEK-601 / WJK (Vancouver East - 40,400) |

WKA / WKK (Vancouver Pt. Grey - 50,000) |

| Gallery - "X" Bloc | ||||

XEA / XKK (Burnaby Office - 60,000) |

||||

As can be seen in the Gallery above, the entirety of the “V--” block had been set aside for the City and its surrounding areas. While not quite the last letter in the new series, it also wasn't the first, which went to Abbotsford drivers. When one Victoria motorist was presented with a rather pedestrian number that started with “VD-” she announced that she would refuse to accept the plates and offered the flimsy reason that she did not want to be associated with Venereal Disease.

He then proceeded to call out the complaint for what it was, noting that people had again turned up at the Branch's Menzies Street office early on the first day to get low numbered plates, that he assumed these people were probably disappointed not to be able to get such plates but, on the bright side, the new aluminum base was designed to last for many years, meaning the plates “would remain easy on the eye, even if they do have VD.” |

As can be seen in the Galleries above, there was some confusion within the Plate Shop at Oakalla as to whether this new series was to employ a dash separator between the letters and numbers. |

On August 30, 1972, the New Democratic Party (NDP) won the provincial election and ended 20 years of rule by the Social Credit and its leader W.A.C. Bennett.

The most notable of these changes was the introduction of a public automobile insurance program, known as the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia (ICBC) the following year (1973).

One of these was the announcement in May of 1973 that license plates would no longer stay with a car as had been the practice since the first automobile registration legislation in 1904. Instead, they would no stay with the individual driver if they sold or traded in their vehicle. If they then bought another vehicle, they would have the ability to register the plates to that vehicle. This change took affect on November 24, 1973.

To help motorists understand the change and prepare themselves, the province undertook an extensive advertising campaign, including multiple, full-page ads in local newspapers, including a dude who has now struck-up a life-long friendship with his license plate. There were some minor hiccups with the introduction of the new system, such as the MVB not issuing refunds for surrendered license plates where the amount was less than $5. Problematic was that the typical refund for a plate expiring between December of 1973 and March 1, 1974, was less than $5. Motorists in this situation were advised that they could either take the loss and surrender the plates, or keep them as a souvenir, but to be very careful how they stored such plates as they were still valid and registered against their name. It was possible that, if grabbed by people with bad intentions, such plates could be used in some nefarious activity and traced back to the unsuspecting owner. For motorists in this situation, the MVB recommended “don't toss those plates around casually. They are your responsibility. If you keep them as souvenirs, make sure they are in a safe place. If you are not going to get another car, destroy them - yes, just like a credit card you don't want. Do a good job so no one else can use them.” |

This was primarily because of the requirement that the sale of license plates be accompanied by the sale of insurance policies, which is something that these municipalities - Hope, Agassiz, Armstrong, Lytton, Summerland, Gibsons, Sechelt, Port Coquitlam, Ladysmith and Lake Cowichan - were not resourced to do. This forced the MVB to find alternate ways to serve these communities, which clearly frustrated MVB Superintendent, Ray Hadfield, when he noted that “a number of these municipalities have wanted to get out of the licence plate business for years. The municipal clerks just didn't want to be bothered, and they figured this was their escape hatch.” Despite this, it was estimated that 50 other MVB sub-offices operated by municipalities would continue to operate under the new system. |

In early 1974, a letter to the Vancouver Sun newspaper commented on a previous article by columnist Allan Fortheringham “about the pettiness of W.A.C. Bennett during the 1972 provincial election campaign ... [being] at an all-time high because his favourite colors, green white (and blue), could be found on the B.C. Railway, B.C. Hydro and its buses, the car licence plates the rash of government adverts, as well as the Socred posters ... It was all supposed to have a psychological influence on the voters to embed in their minds that Social Credit was the government.” |

|

|

|

Having returned to the province after a year-and-a-half absence the writer proceeded to comment on how all of this was being reversed by the New Democratic Party (NDP) of Dave Barrett:

|

|

|

|

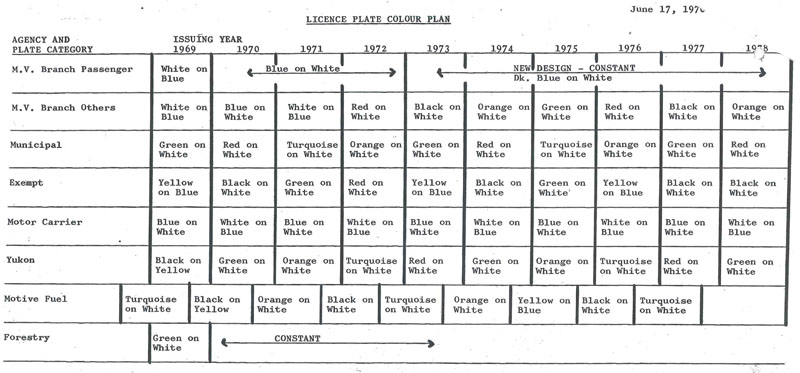

In fairness to the NDP, the decision around the colour of the license plates was not of their making, however fortuitously it might have aligned with their official party colours. Due to the proliferation of various licence plate types that had occurred throughout the 1960s, the Oakalla Plate Shop Business Manager, J.D. White, attempted to project the various colour combinations that would be required throughout the 1970s (approximately 28 colour combinations in total), and did this forecasting a couple of years prior to the NDP's election in 1972: |

So, when a steel shortage occurred in the fall of 1973, the Plate Shop at Oakalla had to prioritize the production of certain license plates for 1974. Ray Hadfield, the Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) advised that, on the basis of experience, motorcycle plates were to be given priority. However, this turned out to be a bad hunch as motorcycle owners held off buying their 1974 license plates to protest the increase in insurance they were going to have to pay to ICBC starting in March of 1974. At the same, an unexpected rush from owners of utility trailers occurred, resulting in a number of MVB offices reporting trouble obtaining such plates. Fortunately, a decision to use decals to renew commercial plates in 1974 was helping with the steel shortage. By early February of 1974, the steel shortage had worked itself out and things were back to normal. |

| Gallery - “LLA” Block | ||||

"LL-"

|

||||

"LS-"

|

"LW-"

|

"LX-"

|

||

"MP-"

|

||||

"MS-"

|

"MT-"

|

"MV-"

|

"MW-"

|

"MX-"

|

"NL-"

|

"NM-"

|

|||

"NW-"

|

"NX-"

|

"PL-"

|

"PM-"

|

|

||

"PS-"

|

"PT-"

|

"RL-"

|

"RM-"

|

"RN-"

|

"RR-"

|

|

"RS-"

|

"RT-"

|

"RV-"

|

"RX-"

|

"SL-"

|

"SM-"

|

"SN-"

|

"SP-"

|

"SR-"

|

"SS-"

|

"ST-"

|

"SW-"

|

"SX-"

|

"TM-"

|

"TN-"

|

"TP-"

|

"TR-"

|

|

"TS-"

|

"TT-"

|

"TV-"

|

"TW-"

|

"TX-"

|

"VM-"

|

"VN-"

|

"VP-"

|

"VR-"

|

|

"VS-"

|

"VT-"

|

"VV-"

|

"VW-"

|

"VX-"

|

"WL-"

|

"WM-"

|

"WN-"

|

"WP-"

|

|

"WS-"

|

"WT-"

|

"WV-"

|

"WW-"

|

"WX-"

|

"XM-"

|

"XN-"

|

"XP-"

|

"XR-"

|

|

"XS-"

|

"XT-"

|

"XV-"

|

"XW-"

|

"XX-"

|

By the third year, however, the new reality had set in and Victoria motorists were adopting the mind set of motorists in all other parts of the province and waiting till the end of February before getting their new decals for 1975 by February 28th.

The decals were later found in a departmental office and Macdonald confessed that “it was a government car, and I just hadn't walked round the back to make sure the new decals were on. They were lying here all right; it was just no one had got around to putting them on the car ... [but] it was my responsibility.”

Macdonald initially advised that he would pay the fine, but was pressed on the topic in the Legislature by Jim Cabot (Socred - Columbia) who asked if the government would be paying? Huh? We get that the Legislature was probably a chummy boys club in this period, but that was a clunker of a joke that probably died on arrival even in 1975 (... we hope). While we suspect that Alex had some explaining to do with his wife Dorothy that night, he wasn't out-of-the-woods with the public yet! After reading of the A-G's travails, a motorist in Prince Rupert wrote to his local paper complaining that he had been fined $25 for the same offence Macdonald had been fined $10 and asked if different fines for different areas of the province.

Upon finding out about this, Macdonald replied to the Prince Rupert motorists and advised that, yes, the fines can vary based on the discretion given to District Judges under the Summary Convictions Act. In another odd decision, Macdonald decided to make things right by declaring himself judge, jury and executioner and fined himself an additional $15, which he donated to the charity of his choice; the United Nation's Children Fund. This strikes us as a bit theatrical on Macdonald' part, and we wonder if this was a donation he would have made regardless and if justice was truly served by his actions? In fairness, Macdonald did advise he would be referring the matter to the Chief of the Provincial Court to see if uniformity in fines could be introduced in future. |

Neighbours reported seeing a station wagon with BC plates being used to transport household items into the San Francisco duplex where Hearst was eventually apprehended by the FBI. “I remember seeing 'Vancouver' on it, somewhere on the back - maybe next to the license plate” said a neighbour, which local media said was confirmed by San Francisco police to be from BC. The next day, the FBI clarified that the station wagon did not display BC license plates (they were California plates) and that there was no evidence that Hearst or any of her comrades had been in Canada.

|

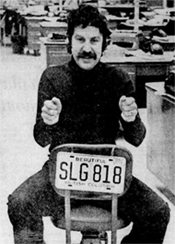

November 1, 1975, also known as the day that ICBC got “punked” by reporter James Spears of the Vancouver Province newspaper.

As part of an investigation instigated by the Province into automobile fraud, it had Spears submit phoney paperwork at a local Autoplan agency for a car that did not exist. Spears made-up the make (1975 Toyota Celica), serial number (TC5DA7980L) and bill of sale along with a bogus signature (“Ashley Forged”). In return, ICBC issued Spears a new license plate (SLG-818) with a 1975 registration decal and a vehicle insurance value of $4,000 which would be paid to Spears if the car was stolen.

This was an obvious problem for ICBC as, apart from having to potentially pay for a non-existent car if claimed to be stolen, such plates could be used on actual vehicles involved in criminal activities (however unlikely as stealing plates would be the easier option) or proof of ownership and collateral for a bank loan. The Province interviewed local RCMP officers who did not feel that “phantom cars” were a big problem in BC (but certainly were south of the border) but that being unable to trace a license plate was becoming a problem. The RCMP preferred the old model where plates had stayed with a vehicle as this allowed for easier identification when an illegal switch had occurred (i.e. plates registered to a Ford appeared on a GMC). Vancouver police also noted that “a small number of Autoplan agents seem to pop up often when 'mistakes' in registration and outright frauds have been uncovered.” In response, ICBC implemented measures to ensure others couldn't follow Spears' blueprint and obtain license plates under false pretenses. As for Spears, he returned the plates 3 days later in order to have the $44 it cost him to register his office chair refunded, which arrived in the mail 6 weeks later with a note; “Return on invalid transaction.” If you are interested what $44 to register a vehicle for 12-months in 1975 is equivalent today, it is $240 (as of 2023)! Of course, the actual cost in 2023 has far outstripped inflation and is probably the equivalent of 5x that amount (i.e. $1,250 to $1,500, if not more). |

| Gallery - “LLL” Block (Oakalla Dies - 1977) | ||||

"LP-"

|

"LR-"

|

|||

"LX-"

|

||||

"MN-"

|

||||

The serial "CDN 110" is one that should not have been stamped onto a 1973 base plate as it fits into neither the LAA (1973), LLA (1975) or LLL (1977) blocks outlined above. The "CDN" prefix is from the "AAL" block, which would only appear for the first time in 1983 (on the 1979 base). So what is this plate and what could it possibly mean? Given that it is displaying Oakalla dies, it could not have been made later than 1977 and some theories suggest it was issued to staff at the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) to mark the 110th anniversary of Canadian Confederation that year (i.e. 1867 to 1977 = 110 years). Whether this is true, or not, has yet to be verified. |

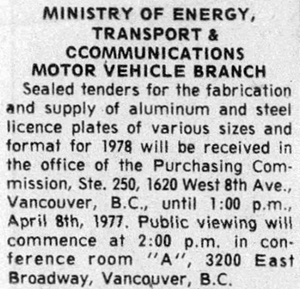

Unlike the Tenders from the 1920s and 1930s, this particular request was light on specifics in terms of the number of license plates required, but apparently this information was available from the Purchasing Commission upon request. It is assumed that the contract would be for a one-year period only (i.e. 1978) and, in a sign of the times, received Tenders would be made available for viewing by the public to ensure transparency and negate the patronage shenanigans that occurred throughout the 1920s and 1930s. A month later, the province issued a separate Tender seeking a company capable of destroying approximately 260,000 pairs of license plates a year for 1978 with an option for 1979. It was estimated that the weight of the recoverable scrap from the plates would be 103,000 pounds of aluminum and 36,400 pounds of steel. While no formal announcement was made on who won the contract to produce the 1978 license plates (or to destroy plate), it is known that ACME Signalisation of Montreal was awarded the contract. We know this because the dies used on license plates can act as finger-prints and the license plate issued by BC in 1978 are using the same dies as the Quebec plates made by ACME Signalisation: This narrower die set is commonly referred to as “Quebec dies” reflecting the location of the ACME facility (no points for creativity on this name), and were used on some other provincial plates (e.g. Newfoundland in the late 1980s). ACME is thought to have produced approximately 300,000 plates for use in 1978 and covered the following serials:

|

1977 Quebec Die Types (0-9) |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1978 British Columbia Die Types (0-9) |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: Quebec switched to a AAA-000 format only in 1983, so it is not possible to compare letters between the two provinces in the late 1970s. |

| Gallery - “LLL” Block (Acme Dies - 1978) | ||||

|

|

"MX-" |

||

"NM-" |

"NP-" |

|

||

"NS-" |

"NV-" |

|

||

"PL-" |

||||

|

|

"PW-" (?) |

"PX-" (?) |

|

|

||

Seeking to grow the business, Brouillette sensed an opportunity in 1975 following a fire that destroyed the license plate making equipment at the Morin & Fils facility in Quebec City. Morin & Fils held the contract for supplying license plates to Quebec at this time, but the fire was delaying the issuance of the province's 1975 series (with the validity of the 1974 plates already extended to the end of April 1975). Brouillette and ACME stepped into the breach and came to terms with Quebec on a contract that to make the province's license plates for the next three (3) years (to 1978), followed by a 3-year extension to 1981 that was reported to be worth a combined $4,000,000. The street sign business was also expanded to provide Montreal, Toronto and the Maritime Provinces road signs as well as signage for the 1976 Olympics, adding a further $3,000,000 in revenue by 1978.

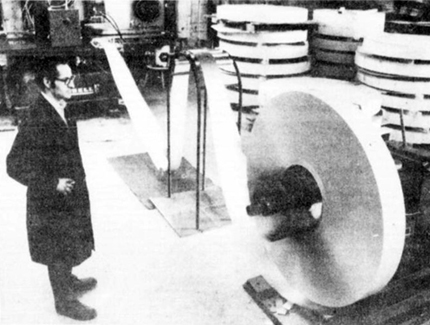

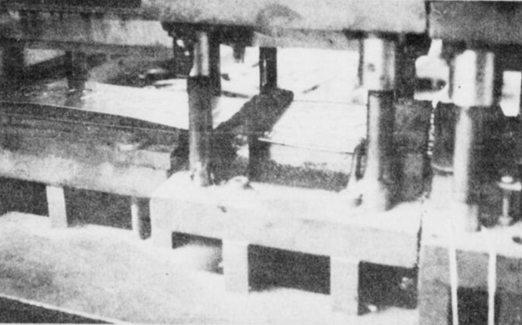

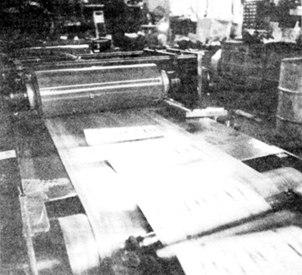

The key to ACME's quick growth was attributed to “la grosse Georgette” (Big Georgette); a stamping press that was built in Quebec to Brouillette's specifications and at a cost of $250,000 ($1,700,000 in 2023 dollars). “La grosse Georgette” was capable producing 50 license plates per minute, 3,000 per hour, 55,000 plates per day, 250,000 per week and one million per month. Even at this rate of production, it took the company eight (8) months to produce the 7.1 million license plates that Quebec needed for 1976. Before investing in “la grosse Georgette”, ACME was making license plates one-by-one and manually changing the characters for each plate - which is basically the way that plates were being made at Oakalla. “La grosse Georgette” streamlined this by cutting the rolled aluminum ACME received from Alcan to the size of a plate and then automatically choosing the dies to be used on the license plates, a process that Brouillette described as “similar to that of the calculating machines, the numbers corresponding to the units being placed one after the other under the press.” Once the plate was stamped, all that remained was for ACME staff to pass it under a roller soaked in paint in the chosen color, pass it through a hot oven and prepare it for delivery. |

|

|

At top-left, a six inch wide aluminum strip from Alcan (0.028 inch guage) is being fed into “Georgette”. In the image to top-right, the plates are “stamped two by two before being cut and painted in two distinct colors. Afterward, they are subjected to a heat of 350°F in an oven where they stay for exactly four minutes. Once the drying is completed, they undergo a numbering verification and are then packaged in a transparent polyethylene bag.” At left, sets of license plates are shown speeding along a conveyor belt towards a packaging area where they will be boxed up and prepared for shipment to the client. |

The resultant economy of scale that ACME achieved with “la grosse Georgette” and supplying millions of plates to Quebec helps to explain how it won the contract to produce British Columbia's license plates in 1978 and to do so at a cost that was 70% of the Oakalla Plate Shop, despite having to ship the order from its factory in Montreal. As will be seen in later years, and despite the initial run of plates ACME produced for British Columbia in 1978, quality control became an issue with “sloppy” become a common description of ACME plates amongst collectors. |

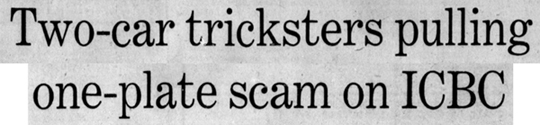

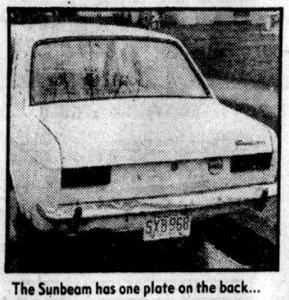

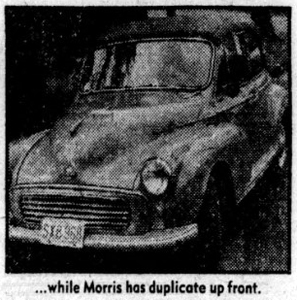

A fraud that has been around as long as there have been license plates received renewed attention by the Vancouver media in early 1978 when it was reported that some motorists were splitting one license plate set between two vehicles in order to save on registration and insurance costs.

The scam was easy to pull off as ICBC was providing motorists with two registration decals throughout the 1970s; one to be applied to the plate on the front bumper and one to the plate on the rear bumper. This allowed a motorist with two cars to place the front license plate on the rear of a separate vehicle, as the decal made it appear that the vehicle was properly registered and with the switch to license plates being assigned to the individual and not the vehicle after 1974, identifying the scam was not easy.

The province combated the practice be levying fines of $15 for anyone caught driving with only a single license plate and a fine of $250 if caught driving an unregistered vehicle and a fine of $250 and potentially 3 months in jail if caught driving an uninsured vehicle. As in the past, this scan usually only came to light if a vehicle was involved in an accident or happened to be randomly stopped by police for a check or some other violation (i.e. speeding). It was estimated that upwards of 5,000 motorists in the province could have been using the scam to defraud the province and ICBC was investigating the merits of issuing only a single registration decal to motorists to combat the practice. As will be seen on the next page (1979-1985), this is exactly what ICBC would do, issuing only single decals from 1980 to 2023. If anyone is interested in which jurisdiction was one of the first to try and combat this scam, check out Tennessee's 1926 license plates and the inclusion of “FRONT” and “REAR” so no one can try splitting them between two vehicles: |

|

|

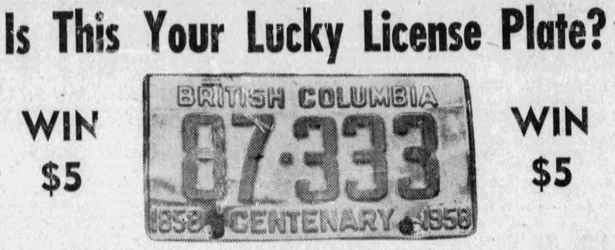

The first time that a license plate may have been used to select the winner of a contest being staged by a local Vancouver media company as a way to boost readership or listener numbers occurred in 1958:

Each day, the newspaper would post the photo of a random license plate, probably taken somewhere around their main office, in order to encourage people to buy that day's paper to see if they were a winner.

It was subsequently reported that:

We suspect this probably earned ICBC some goodwill amongst motorists (if not management at CKLG, who previously got burned in 1970 with their “Freaky License Plates” segment), it also reflects a different era when protecting privacy was not a foremost concern for government agencies. |

| Oakalla License Plate Shop: Postscript |

Out of curiosity, we here at BCpl8s.ca took a look on Google Earth to see what had become of the location of the former Oakalla Prison Farm grounds (including the various locations of the Plate Shop between 1930 and 1977). As can be seen, following the demolition of the prison in the early 1990s, the site was re-developed as a medium density residential neighbourhood. In a nice touch the developers left the front steps that lead into the prison and incorporated a kids playground around them. Which, if you think about it is fitting, as the kids have probably been confined - against their will? - to a specific play area overseen by guard(ian)s: |

|

|

|

|

Quick Links: |

|

© Copyright Christopher John

Garrish. All rights reserved.

In July 6, 1972, the province confirmed that the colour of the 1973 plates would be the same as that used on the 1970 plates; blue-on-white.

In July 6, 1972, the province confirmed that the colour of the 1973 plates would be the same as that used on the 1970 plates; blue-on-white.

Upset at losing the status conferred by having the lowest numbered license plates in the province, Victoria drivers voiced their displeasure by taking issue with the block of plates they did receive.

Upset at losing the status conferred by having the lowest numbered license plates in the province, Victoria drivers voiced their displeasure by taking issue with the block of plates they did receive.  When asked to comment on the incident, Ray Hadfield, Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) expressed surprise that a person would actually be disturbed at the site of such plates as there was a third letter and some numbers. However, if a person felt that strongly about it, they could return the plates to the MVB office in a couple of weeks and “get plates that start with VE or VF or something else.”

When asked to comment on the incident, Ray Hadfield, Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) expressed surprise that a person would actually be disturbed at the site of such plates as there was a third letter and some numbers. However, if a person felt that strongly about it, they could return the plates to the MVB office in a couple of weeks and “get plates that start with VE or VF or something else.”

The new Premier, Dave Barrett (at right), promised a number of changes to how the province would be governed as part of an overall modernization program. The changes enacted by Barrett during his three years in power were extensive and invariably touched upon the production as well as the registration of license plates.

The new Premier, Dave Barrett (at right), promised a number of changes to how the province would be governed as part of an overall modernization program. The changes enacted by Barrett during his three years in power were extensive and invariably touched upon the production as well as the registration of license plates. The new government insurance plan was to come into effect on March 1, 1974, and in the lead-up to this date, the NDP announced new changes required to make sure it was a success.

The new government insurance plan was to come into effect on March 1, 1974, and in the lead-up to this date, the NDP announced new changes required to make sure it was a success.  The reason for this change was that the purchase of public insurance was going to be tied to the renewal or purchase of a license plate.

The reason for this change was that the purchase of public insurance was going to be tied to the renewal or purchase of a license plate.  With the introduction of public insurance and changes to the way license plates were registered, a number of communities that had been assisting the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) with the sale of license plates announced that they would be opting out of this arrangement.

With the introduction of public insurance and changes to the way license plates were registered, a number of communities that had been assisting the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) with the sale of license plates announced that they would be opting out of this arrangement.

In a car culture, any shortage or license plates is truly a crisis as commerce and industry can quickly grind to a halt if transportation networks became gummed up

In a car culture, any shortage or license plates is truly a crisis as commerce and industry can quickly grind to a halt if transportation networks became gummed up

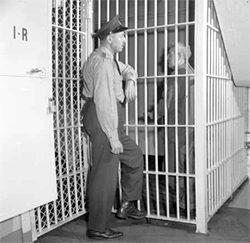

In August of 1974, a brewing controversy at Oakalla appeared in the Letter to the Editor pages of the Vancouver Sun. The writers were the wives of guards at Oakalla and were upset at the low pay; “too low at present to support a family, and far too low to compensate for the unusually difficult and hazardous conditions of the job” - work-life balance and the generally terrible working conditions.

In August of 1974, a brewing controversy at Oakalla appeared in the Letter to the Editor pages of the Vancouver Sun. The writers were the wives of guards at Oakalla and were upset at the low pay; “too low at present to support a family, and far too low to compensate for the unusually difficult and hazardous conditions of the job” - work-life balance and the generally terrible working conditions.

While an agreement was eventually reached, by December of 1974 Oakalla's guards began a work-to-rule campaign in order to collect un-paid over-time wages from the province that had been promised in the new agreement.

While an agreement was eventually reached, by December of 1974 Oakalla's guards began a work-to-rule campaign in order to collect un-paid over-time wages from the province that had been promised in the new agreement.

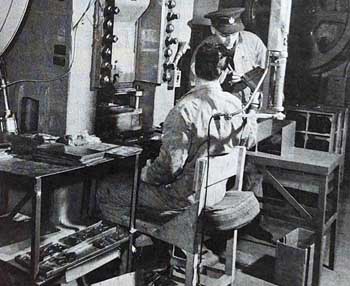

As will be recalled, after an incident in the 1940s in which a prisoner had purposely stuck his fingers into the plate stamping machine in order to get out of Oakalla (and collect a payout), safety measures had been instituted in order to ensure the only digits stamped onto a license plate were numbers.

As will be recalled, after an incident in the 1940s in which a prisoner had purposely stuck his fingers into the plate stamping machine in order to get out of Oakalla (and collect a payout), safety measures had been instituted in order to ensure the only digits stamped onto a license plate were numbers. The guard strike and subsequent need to hire staff to work in the Plate Shop as well as the inflationary pressures that came to define the 1970s also served to blow a massive hole in the allocated budget for the Shop.

The guard strike and subsequent need to hire staff to work in the Plate Shop as well as the inflationary pressures that came to define the 1970s also served to blow a massive hole in the allocated budget for the Shop. According to Barrett, most of the occupational training programs being offered to Oakalla inmates were no shorter than three years in duration, making their successful completion impossible.

According to Barrett, most of the occupational training programs being offered to Oakalla inmates were no shorter than three years in duration, making their successful completion impossible.

Despite the best efforts of the Branch, Victoria motorists had lined up at its Menzies office early on the first day that the 1973 license plates were available in the hopes of receiving a low number, only to be disappointed when handed a plate starting with

Despite the best efforts of the Branch, Victoria motorists had lined up at its Menzies office early on the first day that the 1973 license plates were available in the hopes of receiving a low number, only to be disappointed when handed a plate starting with  One notable Victoria motorist who took this new approach to the extreme was Attorney-General Alex Macdonald (NDP - Vancouver East), who was busted on March 6, 1975, by local Victoria police for driving to work at the Legislature in a car with 1974 decals still displayed.

One notable Victoria motorist who took this new approach to the extreme was Attorney-General Alex Macdonald (NDP - Vancouver East), who was busted on March 6, 1975, by local Victoria police for driving to work at the Legislature in a car with 1974 decals still displayed. Unlike Vancouver Mayor Charles Thompson who was busted 25 years earlier for the same offence of driving on old license plates but was let off without a fine and allowed to continue driving to his destination, Macdonald was issued a $10 ticket and had to walk the remaining distance to the Legislature.

Unlike Vancouver Mayor Charles Thompson who was busted 25 years earlier for the same offence of driving on old license plates but was let off without a fine and allowed to continue driving to his destination, Macdonald was issued a $10 ticket and had to walk the remaining distance to the Legislature. Macdonald cracked that his department had attempted to take responsibility for the slip-up and pay the fine,

Macdonald cracked that his department had attempted to take responsibility for the slip-up and pay the fine,

For a brief moment in September of 1975, a British Columbia license plate was linked to one of the most sensational and high-profile U.S. criminal cases of the decade; the kidnapping and conversion of Patty Hearst (shown at right) by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA)!

For a brief moment in September of 1975, a British Columbia license plate was linked to one of the most sensational and high-profile U.S. criminal cases of the decade; the kidnapping and conversion of Patty Hearst (shown at right) by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA)!

Upon returning to the Province newsroom to write the story of his escapade, Spears posed for a photo with one of the plates mounted to his

Upon returning to the Province newsroom to write the story of his escapade, Spears posed for a photo with one of the plates mounted to his

With the decision to close the Oakalla Plate Shop, the province had to issue a tender for the first time since 1929 seeking a company capable of making license plates.

With the decision to close the Oakalla Plate Shop, the province had to issue a tender for the first time since 1929 seeking a company capable of making license plates..jpg)

As the story goes, ACME Signalisation started off as a small Montreal based sign making business, possibly in the early 1960s, that reliably generated around $100,000 a year in revenue before being acquired in 1971 by Andre Brouillette, a serial entrepreneur (shown at right).

As the story goes, ACME Signalisation started off as a small Montreal based sign making business, possibly in the early 1960s, that reliably generated around $100,000 a year in revenue before being acquired in 1971 by Andre Brouillette, a serial entrepreneur (shown at right).

“

“

20 years later (1978), CKLG (AM 730) launched a “Lucky License Plate” contest that awarded $73 to the car owner whose license plate was called out on air (the equivalent of $315 in 2023), provided they contacted the station within 30 minutes. There was even a “Bonus Call” event that award x10 that amount ($730).

20 years later (1978), CKLG (AM 730) launched a “Lucky License Plate” contest that awarded $73 to the car owner whose license plate was called out on air (the equivalent of $315 in 2023), provided they contacted the station within 30 minutes. There was even a “Bonus Call” event that award x10 that amount ($730).