|

British

Columbia Passenger License Plates

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quick Links: |

In many respects, the challenges and problems encountered in BC during the second decade of the 20th century in terms of licensing motorists and registering their vehicles are no different than those found in other jurisdictions across the country and into the United States. In many instances, governments of this era simply played follow-the-leader and adopted those measures that appeared to work well elsewhere. Accordingly, it is hard to spin a good yarn from this period about BC as many of the decision made here were utlimately based on experiences elsewhere. Fortunately, the Provincial Archives in Victoria possess the outgoing correspondence file of the Superintendent in charge of Motor Vehicles, Colin S. Campbell, for the period in which the province assumed responsibility for issuing license plates. This correspondance provides an interesting insight into the challenges of acquiring a large number of license plates in a period when it was still unkown as to how best manufacture such a product. As the file relates, in the summer of 1912, Campbell had begun investigating what material the first BC plates would be made of. He solicited bids from such companies as the McDonald Manufacturing Company of Toronto, but ultimately chose the McClary Manufacturing Company, which had offices in Vancouver, but which would produce the plates in its London, Ontario factory and ship them via rail to Victoria. The McClary Manufacturing Company had already produced Ontario’s 1911 first-issue porcelains, and very likely made the Manitoba 1911 and Alberta 1912 plates as well, so Campbell was probably familiar with the company’s work. |

|

|

|

|

Shown above left, photos from inside McClary's London, Ontario facility taken around the turn of the 20th Century. While license plates in the stages of production are, unfortunately, not visible, the stoves that McClary was better known for can be seen in the foreground. At middle and right, one of McClary's stoves displaying the same white porcelain that the company would use on its licence plates for Canadian provinces between 1911 & 1914. |

||

Ontario - 1911 |

Manitoba - 1911 |

Alberta - 1912 |

British Columbia - 1913 |

A

certain lack of creativity seems to pervade the McClary

Manufacturing Company's approach to license plate design

in the period between 1911-1913. |

|||

An

initial order of 5,000 pairs of plates was placed, but on

December 4th, it was clear that this allotment would soon

run out and 2,000 additional sets numbered from 5,001 to 7,000

were ordered for delivery by mid-January. |

The McClary Manufacturing

Company seems to have handled the task well, although Campbell

did complain that the plates were not packed consecutively

in the boxes and the numbers on the sleeves holding each set

of plates did not always correspond with the number of the

actual plate. As a result, all of the plates had to be unwrapped

and double-checked before they could be distributed. |

| 1913 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

In

early January, Campbell began distributing the new B.C. porcelains

to his local representatives so that they could be issued

to motorists. Notably, although the plates were ordered from

the manufacturer in pairs, local constables were given a clear

directive to issue only one plate to each motorist. |

It was

clear than the Automobile Act would soon be amended to require

the use of plates on both the front and the rear, but until

that happened, motorists were not to receive pairs. |

Constables

were also instructed to remind vehicle owners that the Automobile

Act required that the plate be placed on the back of the car

in such a position that the vehicle’s lights would shine

directly on it so that it would be plainly visible day and

night. The only vehicles exempt from having to carry license

plates were official fire, ambulance, and police vehicles. |

|

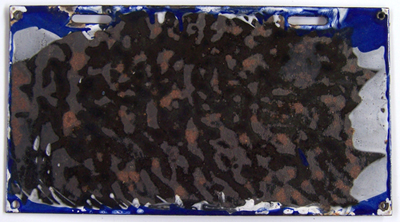

The Back of a Porcelain Plate Ever wondered what was on the back of one of these porcelain plates? Well, here you go ... |

When

the second order of plates arrived from the McClary Manufacturing

Company in late January, Campbell again distributed them to

his constables. Seventeen cases of plates numbering from 6,100-6,600,

for instance, were sent to the Chief Constable of Vancouver

for vehicle owners in that city and its surrounding communities. |

Everything was going according to plan until March of 1913

when the anticipated amendment to the Motor Traffic Regulation

Act was finally passed by the British Columbia legislature

requiring the use of plates on the both the front and the

rear of each vehicle. |

At this point, local constables were

instructed to issue the second of each pair of plates. Campbell

reported that when all was said and done, 5,201 plates were

issued to passenger cars in B.C. in 1913. |

When

it came time to order the new plates for 1914, Campbell again

began making inquiries to determine the best material, price,

and manufacturer. In writing to his counterparts in Washington, Oregon, California, Illinois and Iowa Campbell wanted to know what material

was currently in use there and whether officials and motorists

were pleased with it. |

As he wrote, “this year we are

using enamel and find that many automobile owners complain

that they chip very easily and become disfigured.” Of

course, in the summer of 1913 when this letter was written,

California did not yet have standardized license plates and

the Secretary of State was not really in a position to answer

Campbell’s inquiry. |

|

"Survives Long Burial" A neat newspaper feature regarding the discovery of a 1913 license plates that had been buried for 35 years in the garden of the property at 543 Dunedin Street in Victoria. |

| Colour Variation |

Although very subtle, it is possible to see a minor variation in the blue colour applied to the plates in the higher range of the 1913 series with those possibly higher than 6,000(?) being slightly darker: |

|

|

This particular 1913 plate (No. 729) is purported to have been found on a Vancouver Island beach in 2022. It gives a pretty good indication of how sturdy some of these old porcelain plates are.

|

| 1914 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

On

the advice of the Illinois Secretary of State, Campbell also

wrote to the Adams Seal & Stamp Company of St. Louis,

requesting a catalog for what would have probably been embossed

metal plates. Ultimately, however, the contract for 1914 plates

once again went to the McClary Manufacturing Company at a

cost of less than twenty cents per plate, and porcelain was

once again the material of choice. In the end, as Campbell

reported, 6,688 plates were issued to passenger vehicles in

1914. |

To try and address the chipping of the porcelain that had occurred in 1913, McClary offerred to change the location of the bolt holes and to change the backing of the plates to wood in order to absorb some of the shocks from driving better than the metal backing in 1913 had. Superintendent Campbell rejected the the wood idea as he was concerned that the wood would split and cause other problems. |

As can be seen with the plate shown above, one of the problems with the porcelain plates is that they can easily chip and fracture. It is not known if the damage done to this plate was during its time on a vehicle, or from subsequent storage. |

It

is notable that Campbell was actively pursuing potential contracts

with porcelain manufacturers to supply the 1915 plates as

well. In fact, he seems to have been fairly close to a deal

with the United Enameling and Manufacturing Company of Los

Angeles in May of 1914. The decision to finally go with the

McDonald Manufacturing Company of Toronto was made, in part,

due to the advice of the Deputy Provincial Secretary in Edmonton,

Alberta, who advised Campbell that the lithographed flat steel

plates provided by McDonald to vehicles in that province in

1914 were found to be more satisfactory than the porcelain

plates of the prior two years. |

|

This photo, taken at Queen's Park in New Westminster in 1914, shows plate No. 5157, which was registered to the Terminal City Motor Company of 2242 4th Avenue West in Vancouver. |

*

* * * * |

| Buck's Plates |

This

story came to us through the Vancouver Sun's John Mackie while

he was working on his column about BC license plates, and

involves a collector named "Buck Rogers" who, sometime

in the late 1950s, came across a special commercial garage

near Oak and Marine drive in Vancouver. |

As

Buck passed by the garage one day, he noticed that it was

shingled with literally hundreds of mostly porcelain license

plates on the exterior walls, roof, door as well as the interior

walls, and that all of the plates were, more or less, in numerical

order. Moreover, inside the garage was a bench that ran from

one end of the workshop area to the other, underneath which

were dozens of stacked boxes containing thousands of additional

unissued BC plates. |

Apparently, the garage's owner had once been a BC Government Agent at the local courthouse, which also happened to be the location from which license plates had been distributed to the local community. The Motor Vehicle Branch generally required that all unissued plates be destroyed at the end of the year, and that Agent's submit an affidavit to Victoria confirming as much. |

There

are, however, numerous stories floating around of this not always

occurring and, in this particular instance, it would appear

this fellow decided to shingle his garage with the plates and,

over time, managed to take all the un-issued stock home with

him. |

By

the time Buck came across them, the stacks of plates had been

there for so long that the box material was either completely

rotten or had totally corroded away, leaving only the unused

plates in their original wax paper sleeves. |

So, as any good collector would, Buck approached the proprietors of the garage and queried if "you’re going to take all this to the dump, aren’t you?" |

The guys inside replied that "yes, gradually", they would be taking the plates to the dump, so Buck offered to take it all away for them on the condition that he got to keep whatever he wanted from the pile. |

As

Buck's friend, Rick Percy, relates, these guys thought he was

nuts, but agreed to the deal. |

Buck

then called up his friend Rick and said "I’ve got

to get all these home." So Rick went up and looked at

them and said "Oh my God", to which Buck replied

"Yeah." |

| During his lunch break, Rick would load up his car and take a load down from the garage to Buck's house at 325 Smithe Street in Vancouver, and would do another run after work. This carried for about four days until all the plates had been transfered to the basement of Buck's house. |

According

to Rick, some of the plates were more damaged than the others

because no thought or care had put into their condition when

they had been afixed to the extior of the garage.

|

For

instance, Buck wasn't the only person to have noticed the

garage's unique exterior and during the early years the proprietor

had been approached on numerous occasions be people seeking

to buy some of the plates. So, through the 1920s and 1930s

he put shingle stain on the outside one's in attempt to discourage

people from pestering him. |

Buck

attempted to clean these up and slowly sold them off over

the years, so if you’re at a swap meet and you see a

porcelain BC license plate and you look at it and see there’s

a little bit of brown shingle stain, you know where it came

from |

|

Quick Links: |

Antique | APEC | BC Parks | Chauffeur Badges | Collector | Commercial Truck | Consul | Dealer | Decals | Driver's Licences | Farm | Ham Radio | Industrial Vehicle | Keytags | Lieutenant Governor | Logging | Manufacturer | Medical Doctor | Memorial Cross | Motive Fuel | Motor Carrier | Motorcycle | Movie Props | Municipal | National Defence | Off-Road Vehicle | Olympics | Passenger | Personalized | Prorated | Prototype | Public Works | Reciprocity | Repairer | Restricted | Sample | Special Agreement | Temporary Permits | Trailer | Transporter | Veteran | Miscellaneous |

© Copyright Christopher John Garrish. All rights reserved.

.jpg)