|

British

Columbia Passenger License Plates

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quick Links: |

The period between 1931 and 1976 is considered to be the "Prison Era" when BC plates were manufactured by inmates at Oakalla Prison in Burnaby. |

* * * * * |

It was estimated that 200,000 license plates of all types (cars, trucks, motorcycles and trailers) would be issued in 1949, and that 12,000 to 15,000 of these would be delivered through the mail, with in-person registration starting on February 2, 1949.

|

| Gallery | |||

|

|||

|

|

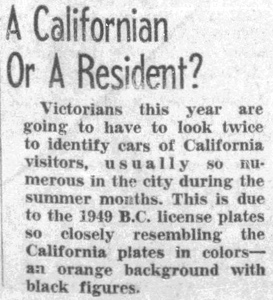

| Despite the care that had been taken in ensuring that the colours on the 1949 license plates did not resemble any others being issued that year, authorities forgot to take into account previously issued plates being renewed through the use of tabs or windshield decals - such as California's 1947 base, which closely resembled the new BC plates. |

In the late-1930s, this seemed to have been fuelled by any envy of California and the hosting of the World's Fair in San Francisco (1939) and in the early 1940s Alberta and its community conscious slogan to "Drive Safely". In 1948, The Province newspaper re-ignited the debate by suggesting that the return of front and rear license plates would be a good as time as any to introduce a slogan, such as "Pacific Playground" or the "North American Norway" or a public contest to pick a better slogan (which would not have been hard).

Predictably, the Abbotsford Chamber of Commerce picked up the baton of having "the Douglas fir or some other suitable emblem or insignia placed on British Columbia auto license plates" for 1949.

Even the British Columbia Federation of Agriculture got involved, debating a resolution calling for permanent car license plates with "distinctive B.C. insignia" at its annual meeting. The Province added its heft in the form of another editorial supporting the BCAA and calling for the introduction of an emblem, such as a totem pole. After scouring its archives, The Province proclaimed the pursuit of a Totem emblem was a long-standing one that had almost come to fruition once:

It is unlikely that a copy of this Thunderbird design was ever found as it is understood that the design the Vancouver Tourist Association pursued in 1940 was an evergreen tree and an accompanying slogan of "Canada's Evergreen Playground". Regardless, the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) took another pass on an emblem and the BCAA complained that "the government seems to lack initiative ... and there has never been any indication of official action." As will be seen, however, events would transpire in favour of an emblem and the next push would finally be the successful one. |

In 1948, the issue of prison crowding and the deleterious affects this was having on young offenders being sent to Oakalla Prison Farm to serve their sentences prompted the provincial government to announce the construction of a new wing in order to segregate young prisoners from hardened offenders.

Due to on-going troubles at Oakalla, the government was forced to revise its plans in March of 1949 and announce the construction of a new 100-cell concrete block at the prison - thought to be what would become known as “Westgate” - in addition to the previously announced renovation of the old jail.

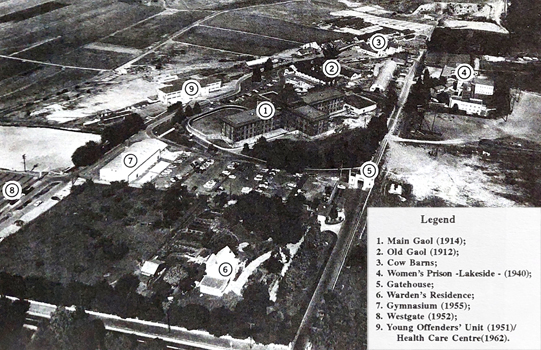

It is thought that the East Wing of the prison is shown circled by the dashed red line in the image at left. Where in this wing the Plate Shop was located is unknown to us here at BCpl8s.ca, but if we had to wager a guess it would likely be in the lower floor / basement(?). As and aside, a quonset hut is a lightweight prefabricated structure of corrugated galvanized steel having a semi cylindrical cross-section, and the government had plans to erect two (2) of them at Oakalla to ease overcrowding. |

|

|

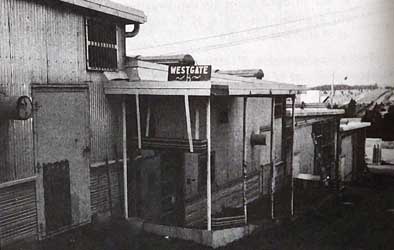

The second Quonset was constructed immediately in front of the first Quonset (as seen in the image at lower-right) and they must have been provided with internal connections. Some clues as to the order ar the windows on the side of the first Quonset and the number of vents at the top of each (4 on the first and 7 on the latter). The top photos of the Quonsets are stated as being sometime in the 1950s, but we think they are just a little bit earlier than that (certainly the first one is). The Quonsets are sited due north of the old jail and were retained up until the demolition of Oakalla in 1991. |

|

When the planned “new jail” was completed, the 100-cells in the concrete building then under construction (“Westgate”) would be removed with this structure becoming “the permanent workshop for the prison farm.” The Attorney-General described it as being a place where young men could be “segregated in a sort of Borstal and kept there until it is determined they are suitable for Borstal home at New Haven” (Borstal being a reference to a system started in England for rehabilitating young offenders that was popular at this time). |

|

|

Shown above (left) is a photo of the front of WestGate “B”, where all of the various Oakalla shops were relocated to in the early 1950s, including the Plate Shop. At top-right is an image of the Westgate roof taken from Royal Oak Avenue in the early 1950s and looking out to Deer Lake in the background, and showing the low-flung design of the structure. |

|

* * * * * |

As the guards in the Plate Shop worked closely with inmates they were not provided with weapons (guns) and when the prisoner made his break for the fence and woodlands beyond, there was not much they could do other than give chase (but they were evidently not as fleet of foot). * * * * *

|

|

Thanks to Earl Anderson's excellent book Hard Place to do Time: The Story of Oakalla Prison: 1912 - 1991, we have access to a site plan that helps orient the various locations of the Plate Shop as it was moved around the Oakalla site in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The West Wing of the main jail is seen at the No. “1”, the quonset huts used in 1949 & 1950 can be seen immediately below the cow barns at No. “3”, while the corner of Westgate can be seen at No. “8” (at far left). |

* * * * * |

| 1950 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

On December 21, 1949, it was announced that the colour of the 1950 license plates would be the reverse of the previous year's plates; "yellow numbers on a black background." It was estimated that 220,000 license plates of all types (cars, trucks, motorcycles and trailers) would be issued in 1950 - being another new record! |

| 1950 | |||

|

|||

Since the switch in the licensing year from the end of December to the end of February in 1933, the Provincial Police had steadily phased out the informal grace period of 2-weeks they had previously granted motorists to obtain their new license plates, which the following headlines from the proceeding 16 years attest:

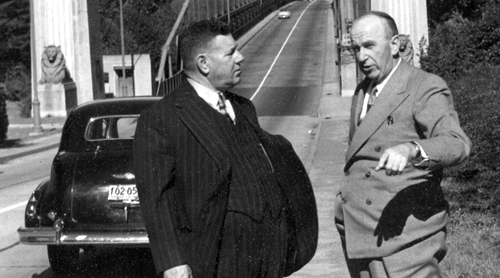

So, when the Mayor of Vancouver, Charles Thompson, was caught driving with his 1949 plates and drivers license on March 12th - nearly a full two weeks after the deadline for obtaining 1950 plates! - the story was carried far and wide, including in the national media. According to Thompson, he was touring some of Vancouver's newly paved street with his wife when the wail of a police siren brought him to a stop. A young office got out and asked him a question he already knew the answer to; "Driving with last year's plate, eh", before asking for the Mayor's driver's license. When the Mayor identified himself, the police officer "nearly fainted" and "didn't wait long enough to find out that the mayor not only was using last year's plates but also had forgotten to pick up his new driver's license." Thompson instantly caught flack for using his position to get out of a summons to traffic court (as was the practice in this period) that anyone else in the same position would have received.

To diffuse the situation, Thompson arranged to pay the typical fine of $10 for this type of infraction directly to the Chief Constable, thereby avoiding traffic court. After the story was picked by the Toronto Globe and Mail newspaper, Thompson received a letter from Judge J.A. McGibbon of Lindsay, Ontario, who had seen the story and sent Thompson a $1 contribution towards his fine. Lindsey had met Thompson the previous summer when he was toured around Vancouver in the Mayor's official vehicle and thought this was the car Thompson had been driving when pulled over. Lindsey added a “PS” to the letter; he couldn't guarantee financial aid in the event of a second offense. Thompson would serve only two years as Vancouver Mayor, losing the December 13, 1950, civic election to Frederick Hume. |

|||||||

The lucky motorist was Rick Paschal, a used car salesman in Vancouver who had the plates on a demonstrator model. We suspect that Paschal was hoping the novel number would help him quickly sell the vehicle it was attached to (and maybe even at a premium) given his first action was to promptly phone The Province newspaper to apprise them of his score. The next day, the Vancouver Sun newspaper clarified the situation for any its readers who might have been tempted to go and purchase the car with the No. 200-001 plates from Paschal. The No. 200-000 (a more momentous number) was still sitting in the Victoria office of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) waiting to be sold, while numbers higher than No. 200-001 would still be issued before the end of the year. There were also 10,000 plates lower than the No. 200-000 still waiting to be issued in the Vancouver area alone, while registered vehicle numbers were only at 169,000 for the year. |

* * * * * |

This prompted the Vancouver Province newspaper to begin advocating for something similar in British Columbia, given the savings could be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, in addition to the annual hassel of having to replace one's license plates. The solution was one that had been used in BC previously; either a metal renewal tab (as had been used in 1919 and 1921-22) or a windsheild sticker (1933-34). Five months later, in September of 1949, the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) announced that it was studying the idea of a “permanent” license plate by surveying other jurisdictions on their systems, but the soonest this could happen would be 1951 as the 1950 license plates were already being manufactured at Oakalla:

MVB Superintendent, George Hood, remained skeptical of such a license plate - “It doesn't look as easy as it appears on the surface” - as BC provided for a reduction in license fees if plates were not purchased for a full year. For example, if a car owner stored his vehicle in a garage for the first three months of the year, they were given a quarter reduction in their license fee. If British Columbia moved to a permanent plate, Hood was concerned that motorists “would be much more likely to take the chance of driving his car in this period when he actually had not paid the fee” and noted that some places with a “permanent” plate did not allow for such a fee reduction. Counterfeiting, accounting costs and administrative efficiencies were also weighing on Hood.

The Vancouver Sun newspaper opined that “it is to be hoped the [Motor Vehicle Branch] won't decide to perpetuate the depressing funeral yellow-on-black chosen for the 1950 plates” and suggested Gold-on-Blue, being the colours of the University of British Columbia (UBC) for the new permanent license plates.

The 5-year plates, which were to be made of a new material and with a new design would be issued in 1952. Additional information regarding these new 5-year license plates is available on the following page (1952-1954).

|

| 1951 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Registrations were anticipated to climb from 198,000 (1950) to almost 210,000 (before ultimately reaching 213,770 by the end of 1951), however due to the near invisibility of the registration numbers stamped into the tabs, it is difficult to know how many were ultimately produced. |

.jpg) Short Version (length: 10 3/4 inches) |

.jpg) Long Version (length: 12 1/2 inches) |

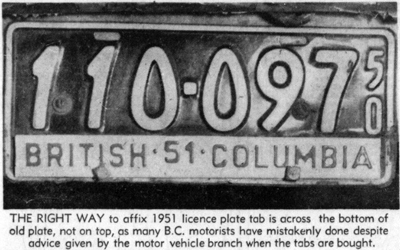

Consequently, a whole generation of car owners had no experience with the practice and the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) tried to rectify this situation with the assistance of local newspapers by running photos show how to affix the 1951 tabs to the 1950 license plate. Shown at right is F.T. MacDonald Lake of the Vancouver MVB office showing how the tab is to be affixed to the bottom of the plate. Easy, right? Well, apparently not as, in a portend of the troubles to come, Mr MacDonald Lake is attempting to fit a short version of the tab intended for a 5-digit license plate to the longer 6-digit license plate! |

|

|

The government was serious as two Victoria residents, Morris Duke and Edgar Perry, soon found out when, “in the first case of its kind”, they were fined $10 each in police court for wrongly affixing the 1951 validation tabs on the top of their license plates. * * * * *

* * * * *

A week later the local press had picked up the story, quoting “veteran police officers” who stated “the new strip is just what license thieves have been dreaming of for years" and dozens of reports of thefts of the strips had already been reported to the police. The police placed less emphasis on the old-fashioned cheapskate who saw an opportunity to register a single vehicle but swap out the 1951 renewal tab to other cars they might have owned. Also irking the police was the “almost undecipherable stamp, [and] a lengthy serial number” that were making it impossible to easily determine if a tab was stolen, or a counterfeit (but, given how easy they were to steal why would anyone bother making a knock-off?):

To try and deal with the issue, motorists were advised to place the “green slip” that they had received with their 1951 tabs in a conspicuous place inside a car so that it could be checked against the license plate whether a motorist was in their car, or not. Failure to display the green slip could result in a $5.00 fine. |

||||

The Provincial Police had been tasked with administering vehicle registrations in the province since the first legislation had been adopted in 1904 and had built up an elaborate system comprising dozens of field offices throughout British Columbia to fulfil this mandate. With the dissolution of the Provincial Police, the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) was retained by the Attorney-General's office, but the RCMP had agreed to carry-on certain tasks that the Provincial Police had previously for an interim period, such as vehicle registrations, collection of dog taxes and issuance of marriage and birth certificates while alternate arrangements were made.

In Sechelt, Gibsons and Kimberley motorists were reported to be protesting by continuing to drive their vehicles with 1950 plates after the March 31st deadline for obtaining the 1951 renewal tabs and refusing to pay the fines they were being issued for doing so. Wismer advised the Legislature that the job of the police was law enforcement and they should not have been providing these other services and motorists should not have been ticketed. Going forward, alternate arrangements would be made for vehicle registration while those who had been ticketed for not yet having 1951 tabs in the smaller “country areas” of the province would have these cancelled. |

Due to a reported steel shortage in May of 1951, the material used on the additional 1950 base plates required for the 1951 licensing year was switched from metal to aluminium for plates issued after the No. 230-000. This also happened to be the same material that was being used in the manufacture of the new 1952 license plates. While it is difficult to convey in a picture, the plates shown below are all made of aluminium: |

Quick Links: |

|

© Copyright Christopher John Garrish. All rights reserved.

On November 19, 1948, it was announced that the colour of the 1949 license plates would be "deep yellow ... with black lettering. The colors are just a little different from any chosen in North America. Manitoba's plates will be nearest, with black on ordinary yellow ... Texas has gone everyone just a bit better: her cars will be tagged with gold plates bearing black letters."

On November 19, 1948, it was announced that the colour of the 1949 license plates would be "deep yellow ... with black lettering. The colors are just a little different from any chosen in North America. Manitoba's plates will be nearest, with black on ordinary yellow ... Texas has gone everyone just a bit better: her cars will be tagged with gold plates bearing black letters." Superintendent George Hood also assured motorists that "as far as it's humanly possible, I think I can say the paint won't peel this year." This was because the plates had "been put through 14 days in a weather testing machine. The test, equivalent of a year's weathering, showed the effects of cold, heat, fog and ice on the paint." Hood continued that the plates "came out a little dulled from the machine, but all license plates do that after a year of weathering."

Superintendent George Hood also assured motorists that "as far as it's humanly possible, I think I can say the paint won't peel this year." This was because the plates had "been put through 14 days in a weather testing machine. The test, equivalent of a year's weathering, showed the effects of cold, heat, fog and ice on the paint." Hood continued that the plates "came out a little dulled from the machine, but all license plates do that after a year of weathering."

When the provincial government took a pass, the The Province lamented that "Victoria's resourcefulness seems to extend only to color schemes" and laid down a new challenge; "by 1949 we should try to send a symbol with our license plates. Let us design a little colored totem pole, or a tree or a motto that will briefly convey to strangers the beauties of our province."

When the provincial government took a pass, the The Province lamented that "Victoria's resourcefulness seems to extend only to color schemes" and laid down a new challenge; "by 1949 we should try to send a symbol with our license plates. Let us design a little colored totem pole, or a tree or a motto that will briefly convey to strangers the beauties of our province." They were joined two months later by the British Columbia Automobile Association (BCAA), who also proclaimed "we should have a slogan or an emblem" and began lobbying the provincial government to include an evergreen tree - provided the plates "don't peel" (ouch!).

They were joined two months later by the British Columbia Automobile Association (BCAA), who also proclaimed "we should have a slogan or an emblem" and began lobbying the provincial government to include an evergreen tree - provided the plates "don't peel" (ouch!). The Attorney-General, Gordon Wismer, informed the Legislature that "the old wing of the jail used for the manufacture of auto license plates will be completely renovated and set aside for housing young offenders. A new building will be put up for plate manufacture."

The Attorney-General, Gordon Wismer, informed the Legislature that "the old wing of the jail used for the manufacture of auto license plates will be completely renovated and set aside for housing young offenders. A new building will be put up for plate manufacture." The work on the West Wing of the main jail was nearly completed by March of 1949, and Wismer advised that the East Wing would be converted to cells "as soon as the license plate machinery now housed in that section of the old building has been moved to a newly erected quonset hut", which was tentatively due to be completed within weeks.

The work on the West Wing of the main jail was nearly completed by March of 1949, and Wismer advised that the East Wing would be converted to cells "as soon as the license plate machinery now housed in that section of the old building has been moved to a newly erected quonset hut", which was tentatively due to be completed within weeks. Shown above are the Quonset huts at Oakalla. While details are not easy to come by, it is felt that the Quonset shown at left was the first one constructed in 1949 and the temporary home of the Plate Shop after it was moved out of the old jail and while new facilities were constructed elsewhere.

Shown above are the Quonset huts at Oakalla. While details are not easy to come by, it is felt that the Quonset shown at left was the first one constructed in 1949 and the temporary home of the Plate Shop after it was moved out of the old jail and while new facilities were constructed elsewhere.  An interesting insight into the operation of the Plate Shop at this time comes from news reports of prisoner escape at Oakalla which occurred on April 30, 1949, at 11:30 a.m. as inmates employed in the shop were being lined up lunch.

An interesting insight into the operation of the Plate Shop at this time comes from news reports of prisoner escape at Oakalla which occurred on April 30, 1949, at 11:30 a.m. as inmates employed in the shop were being lined up lunch.  By May of 1950, the Plate Shop had left the confines of the quonset huts as these were now being put to use housing 146 Doukhobors awaiting transfer to a penitentiary. It was reported that the huts could accommodate up to 200 persons and that the Doukhobors “present no problem at the prison ... [and that] only four extra guards have been hired.”

By May of 1950, the Plate Shop had left the confines of the quonset huts as these were now being put to use housing 146 Doukhobors awaiting transfer to a penitentiary. It was reported that the huts could accommodate up to 200 persons and that the Doukhobors “present no problem at the prison ... [and that] only four extra guards have been hired.”

Twenty years after the province issued the first 6-digit license plate bearing the No. 100-000 (in 1930), the first plate with a number above 200-000 was issued on September 8, 1950.

Twenty years after the province issued the first 6-digit license plate bearing the No. 100-000 (in 1930), the first plate with a number above 200-000 was issued on September 8, 1950.

In 1949, both Oregon and Washington State had announced that they were moving to a “permanent” license plate system in which the same base plate would be used for a period of between 2 to 5 years.

In 1949, both Oregon and Washington State had announced that they were moving to a “permanent” license plate system in which the same base plate would be used for a period of between 2 to 5 years.

In February of 1950, it was announced that “a system of semi-permanent license plates for automobiles will probably be adopted by B.C.” starting in 1951. It was thought the plates would be issued for 5-years, but specific details would have to await the sitting of the Legislature the following month.

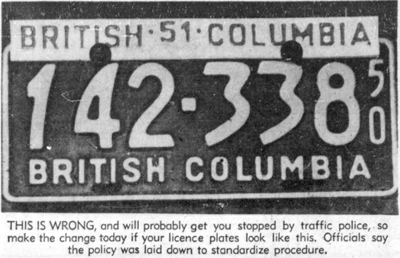

In February of 1950, it was announced that “a system of semi-permanent license plates for automobiles will probably be adopted by B.C.” starting in 1951. It was thought the plates would be issued for 5-years, but specific details would have to await the sitting of the Legislature the following month. When the legislative amendments were introduced in March of 1950, it was revealed that the new system would be for 5-year license plates as well as 5-year driver's licenses. Importantly, and prior to the introduction of the 5-year plate, there would be a one year transitionary period in which motorists would not be given new plates but instead “a tab covering the bottom section of their [1950] plate and reading ‘British 51 Columbia.’”

When the legislative amendments were introduced in March of 1950, it was revealed that the new system would be for 5-year license plates as well as 5-year driver's licenses. Importantly, and prior to the introduction of the 5-year plate, there would be a one year transitionary period in which motorists would not be given new plates but instead “a tab covering the bottom section of their [1950] plate and reading ‘British 51 Columbia.’” Blowing its own horn, the Vancouver Province newspaper reminded its readers that "for two and a half years this newspaper has been after the Provincial Government to provide B.C. automobiles with permanent, heavy-duty license plates and eliminate all the work and trouble of annual renewals.” Now that such plates were coming, the newspaper was humbly “glad it was able to do its bit in stirring the government into action, but regrets it takes officialdom so long to warm to new ideas.”

Blowing its own horn, the Vancouver Province newspaper reminded its readers that "for two and a half years this newspaper has been after the Provincial Government to provide B.C. automobiles with permanent, heavy-duty license plates and eliminate all the work and trouble of annual renewals.” Now that such plates were coming, the newspaper was humbly “glad it was able to do its bit in stirring the government into action, but regrets it takes officialdom so long to warm to new ideas.” The new tabs (also referred to as strips) that were to be used in 1951 were to be white with blue lettering and would be manufactured in two different sizes for use on the shorter 5-digit plates and longer 6-digit plates.

The new tabs (also referred to as strips) that were to be used in 1951 were to be white with blue lettering and would be manufactured in two different sizes for use on the shorter 5-digit plates and longer 6-digit plates. The last time BC motorists had been asked to use renewal tabs to re-validate a license plate had been in 1922.

The last time BC motorists had been asked to use renewal tabs to re-validate a license plate had been in 1922.  Even more interesting was the the provincial government heavy-handed response to what can only be seen as a very mild act of protest. An Order in Council (OIC) was passed amendment the regulations to the Motor Vehicle Act making it an offence to place the tab anywhere other than the bottom of a license plate!

Even more interesting was the the provincial government heavy-handed response to what can only be seen as a very mild act of protest. An Order in Council (OIC) was passed amendment the regulations to the Motor Vehicle Act making it an offence to place the tab anywhere other than the bottom of a license plate! Given the novelty of renewal tabs for many motorists, we suspect the following misunderstanding afflicted both men and women. The press, however, only reported on the case of three female drivers in Courtenay who had bought the 1951 renewal tabs at the local MVB issuing office and, in an ultimate act of protest, promptly threw away their 1950 license plates and mounted only the tabs on their cars.

Given the novelty of renewal tabs for many motorists, we suspect the following misunderstanding afflicted both men and women. The press, however, only reported on the case of three female drivers in Courtenay who had bought the 1951 renewal tabs at the local MVB issuing office and, in an ultimate act of protest, promptly threw away their 1950 license plates and mounted only the tabs on their cars. An innocuous classified ad placed by Black Motors Limited in February of 1951 hinted at an early problem with the renewal tabs; they could be easily stolen!

An innocuous classified ad placed by Black Motors Limited in February of 1951 hinted at an early problem with the renewal tabs; they could be easily stolen!

.jpg)

On August 4, 1950, the BC Provincial Police ceased to exist and were replaced by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

On August 4, 1950, the BC Provincial Police ceased to exist and were replaced by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).  At the end of 1950, the RCMP had decided to end its provision of these ancillary services in four or five towns, but neglected to inform the provincial government. As a result, “a minor storm broke over Attorney-General [Gordon] Wismer's head in the Legislature [in early April of 1951] ... as members complained that RCMP would not issue motor licenses and hundreds of people couldn't get their 1951 plates at outlying points.”

At the end of 1950, the RCMP had decided to end its provision of these ancillary services in four or five towns, but neglected to inform the provincial government. As a result, “a minor storm broke over Attorney-General [Gordon] Wismer's head in the Legislature [in early April of 1951] ... as members complained that RCMP would not issue motor licenses and hundreds of people couldn't get their 1951 plates at outlying points.”