|

British

Columbia Passenger License Plates

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quick Links: |

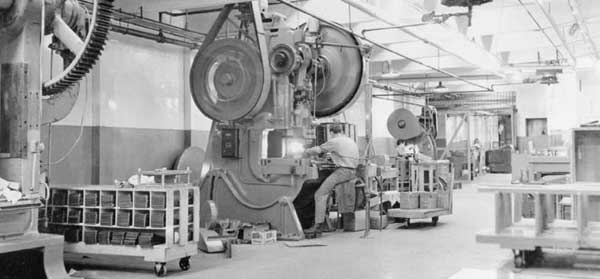

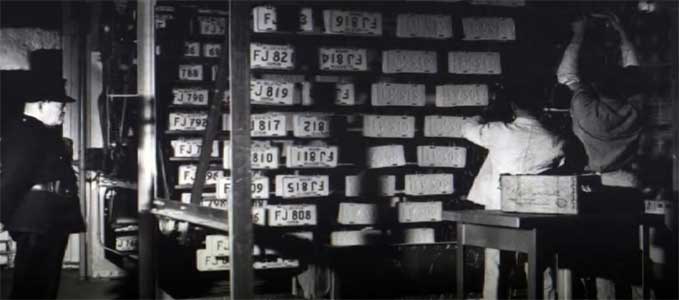

The period between 1931 and 1976 is considered to be the “Prison Era” when BC plates were manufactured by inmates at Oakalla Prison in Burnaby. |

* * * * * |

In an astounding about-face from its editorial printed a mere four years earlier decrying “the folly of doctoring up licence plates to suit boosters and promoters” with slogans and emblems, the Vancouver Sun commended Quebec's introduction of its “La Belle Province” slogan on its 1963 license plates by asking “why not British Columbia?” The Sun's editorial staff noted that “almost every one of the United States has adopted this simple but effective form of huckstering - The Empire State (New York), Water Wonderland (Michigan) and so one ... Now what could B.C. be?” Nine days later, on August 30, 1962, the provincial government answered the question by announcing that the 1964 license plates would include the slogan “Beautiful”.

It was further announced that the colours for the 1963 and 1964 plates would be blue and white; “a clear-cut color scheme everyone should welcome” after the wild colours of 1959-1962. Yet, in another head-scratching about-face, the Vancouver Province newspaper, a reliable supporter of all license plate slogans and emblems in years past, splashed cold water on the “Beautiful” slogan:

Of course “someone” could! Cue Harry Duker: |

|

The Vancouver Province's plea had “renewed [Duker's] dormant hope that eventually a suitable name will be added to British Columbia licence plates ... [and] I have never changed my belief that the word 'Totemland' most adequately describes our province.” Duker noted that “Totemland” comprised the same number of letters as “Beautiful” and could easily be made to fit on a license plate and anyone who agreed with him should write to the B.C. Government Tourist Bureau at the Parliament Buildings in Victoria. While Duker would write a few more letters to the newspapers in support of “Totemland”, the slogan question went cold for the remainder of 1962 and 1963. |

| 1964 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

It was anticipated that over 700,000 license plates would be required, Earle Westwood, now the Minister of Recreation and Conservation, would later announce that blue and white would be the permanent colours used on BC license plates, similar to the colours used on the B.C. Toll Authority ferries (shown at right). |

| Gallery | |||

|

|

||

|

|||

Seemingly forgetting the 1958 "CENTENARY" slogan and that P.E.I. (along with Idaho) was the first jurisdiction in North America to place a slogan on its license plates in 1928, Nicol asked where the idea came from. He then answered his own question by stating; “from the States, of course. No bureaucratic pea-brain is too small to be impressed by the fact that some American states have yielded to this hucksterism, and therefore, nothing will do but that the Canadian province apes them ... A means of blowing our own horn is standard equipment on most automobiles. We do not need or, I hope you'll agree, want the anything-but-divine afflatus of licence platitudes.”

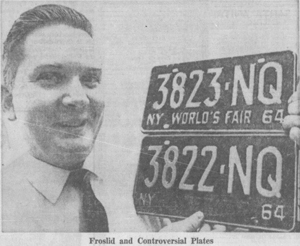

Froslid proclaimed that “I've nothing personal against the world's fair. What stirred me up was the arbitrary way the legend was put on the plates in the face of some serious questions of law. The state has no right to compel me - without even asking - to carry free advertising on my car.” What made the story newsworthy to the Province and Daily Times was that a state supreme court justice agreed with Froslid and that he was entitled to new, slogan-free plates. Seemingly encouraging its readers to follow Froslid's lead, the Province planted a very suggestive seed by commenting that should “a motorist decide to take matters in his own hands and remove the [“Beautiful” slogan] let him be warned: The Act says the plates remain the property of the Crown.”

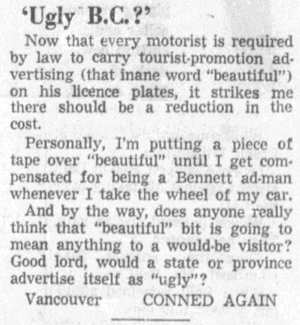

While there is no known evidence of anyone actually covering up the “Beautiful” slogan with tape the way Froslid did to New York's “World's Fair” slogan, some motorists certainly talked about it the Letter to the Editor pages of the major newspapers, such as “CONNED AGAIN” (see at right). Why the Superintendent of Motor Vehicles decided to respond to a crank Letter to the Editor is beyond us here at BCpl8s.ca, but that is precisely what George Lindsay decided to do after reading “CONNED AGAIN”.

Not missing a beat, or the chance to sell more newspapers by further engaging its readers in this newest of license plate bun-fights, Eric Nicol's rushed to “CONNED AGAIN”s defence, overwroughtly declaring:

Whereas, a “SUBSCRIBER” from Vancouver (see at right) took issue with Nicol's muckraking and anyone else who would obscure the “Beautiful” slogan on their license plates. And with that, the controversy petered out. The appear to be no records of any summons to traffic courts for motorists who got caught covering up the “Beautiful” slogan, or any plates that have survived in collections where the slogan was defaced (at the time). Four months later, in announcing the colours and design of the 1965 license plates in July of 1964, the province settled the slogan debate:

|

Duker had come to Vancouver from Missouri in 1907 to play baseball for the Vancouver Beavers in the northwestern league. When he was cut from the team as a player, one of the teams directors is reported to have said “that kid's got the gift of the gab, let's send him out to sell advertisements for the program.” From this, Duker parlayed his advertising skills into an outdoor billboard business that he sold for $300,000 in 1928 (on the eve of the Great Depression), and promptly retired at the age of 42. Duker would spend the next 50 years in community service, volunteering on various board and committees, including the Vancouver Parks Board, Vancouver Tourist Bureau, BC Committee on Human Rights, Metro Commuters' Council, BC Automobile Association, Greater Vancouver Communities Council, as a founder of the Vancouver Aquarium and, of course, the Totemland Society.

The irony of this decision, and likely unbeknownst to Duker's family at the time, was that Edward Simmons (being the Simmons in “Simmons & McBride”) had been the most vocal opponent of Duker's quest to get “Totemland” included as the slogan on BC license plates in the 1950s! Simmons (shown at right), was no slouch either when it came to membership in various groups and clubs, including the Gizeh Temple, Vancouver Lodge, Knights of Pythias, RCMP Veterans Association, Terminal City Club (Life Member), Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, Canadian Club and the Vancouver Board of Trade and Junior Chamber of Commerce. At the time of Duker's death in 1982, Simmons had been dead for eleven years, having passed in March of 1971. |

For eagle eyed plate collectors, the introduction of the “Beautiful” slogan was not the only new addition to the plates that year. For whatever reason, it had been decided to go with a smaller die for the provincial name (“BRITISH COLUMBIA”). Even more interesting is that the old, longer “BRITISH COLUMBIA” die used as early as possibly 1952, but certainly from 1955 through to 1963 would re-appear throughout the 1964 series - and there is no rhyme nor reason to its use. Don't believe us? Take a look at the No. 58-000 plates shown below. This is one of the only known examples of where the different dies appeared on the same plate number. |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Palindrome: "a word, phrase, or sequence that reads the same backward as forward" - and also a fun subset of license plate collecting for the truly dedicated. |

|

A fun posting on social media in 2024; a Mudlarker walking along the Fraser River today found an old 1964 BC plate that appears to have been unearthed along the banks of the river by shifting currents (or something like that). All things considered, for potentially being buried along the banks of the Fraser for the past 60 years, the plate is in not that bad a shape! |

* * * * * |

| 1965 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

This was because it was estimated to be more efficient to issues plates over the counter than by mail (in terms of staff time and money). So, to encourage motorists, the Branch announced that mailed requests - estimated to number around 32,000 per year - would be issued a license plate number above 567-501 (as shown by Dianne Ward, MVB Clerk, at left). In previous years, mail requests had received low numbers. For those motorists who had received a number from 2 to 3,000 in 1964, they had until the end of January 1965 to re-claim it, after which it would be assigned to one of the 800 people on a wait list maintained by the MVB for low number requests. To stymie thieves, motorists were also reminded to keep their expired 1964 plates indoors until March 1st so the plates could not be used on stolen vehicles. Finally, the Trail Chamber of Commerce (of all organizations!) channeled a 1930s marketing vibe and suggested the 1966 BC license plates should be green and include an evergreen tree emblem! |

| Gallery |

* * * * * |

| 1966 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Staying with the policy of rotating blue-and-white colour schemes, the 1966 license plates were the reverse of the 1965 colours and, despite continued chatter, would not use reflectorized paint or become permanent. In continuing to encourage in-person registrations, mail order registrations would be issued plates numbered above 590-000 in 1966. Towards the end of the year, as vehicle registration numbers climbed towards 700,000, the MVB indicated a likely move toward an alpha-numeric serial number (e.g. AAA-000) by 1970, similar to what California and Washington used. More on this in the next page (1970-1978). |

| Gallery |

The Saskatchewan Roughriders entered the game having never won the Cup and, in the lead up to the cahmpionship game, Vancouver authorities decided to hold the traditional Grey Cup Parade on the night of November 25, 1966 (a Friday).

150,000 people attended the Parade, but afterwards some of them went wild and police fought three pitched battles with rioting fans (we would like to think it was Prairie folks, but Vancouverites have a history of rioting around major sporting events), arresting 443 in total, while significant property damage occurred.

When the riot broke out, a “souvenir hunter” reportedly snatched one of the No. 1 plates off of Sivertz's car. The cost to replace the plate was estimated to be $100 (almost $900 in 2023 dollars - which seems nuts!), and since they were to be used for three-years (to the end of 1969) it was decided to retire the number and issue Sivertz a new number. Fast forward 57 years, and the 1966 No. 1 plate finally re-surfaced, and it was still in Vancouver (in a private collection):

|

* * * * * |

| 1967 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

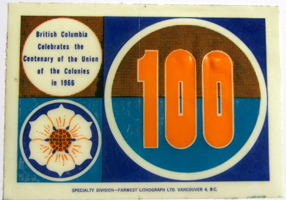

For certain generations of Canadians, the centennial of the Canadian state in 1967 was a BIG deal (the last good year if you read Pierre Burton ... but we don't read Burton and think his claim is bollocks!).

Nevertheless, the importance of the event can be seen in the fact that half the provinces and territories - including Quebec! - decided to mark the occasion on their license plates. Generally, these commemorations were overt and included text and dates reflecting the event:

Otherwise the basic design of the plates remained unchanged, as did the continued use of the “Beautiful” slogan. Due to the continued growth in car ownership, license plate numbers exceed 700,000 for the first time. |

| Gallery |

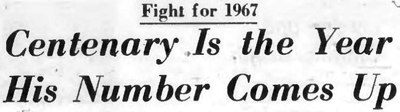

When it was revealed that the No. “1967” had been held by Burnaby resident and Vancouver dry cleaning business owner Norman Chan since 1961 or 1962, it was suggested that the numbers (shown at right) be held back for publicity purposes and not be issued.

Full kudos, however, to MVB Superintendent Ray Hadfield who advised that “despite pressure from some unnamed sources, he [intended] to maintain the Branch's established policy by reserving plates 1967 for Mr. Chan.” By December of 1966, Chan's application to the MVB for the plate was in mail, along with an anticipated 35,000 other applications, and Chan hoped to be issued the number again “to have it when it really means something.” |

On the last day of February 1967, which was also the last day that motorists could legally drive with their 1966 plates still on their car, the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) office at the Brentwood shopping centre in Burnaby shut their doors 30 minutes early to serve those already in the office. This left over 150 people unable to get their new license plates - and likely guaranteeing they would be fined by the police for driving with expired plates. When it appeared that a riot was about to happen (doors were being “angrily rattled” and wickets “shook”), panicky MVB staff called the police and four cars of RCMP officers were dispatched to quell the brouhaha.

The day had not started well when MVB staff arrived at 9:30 a.m. to discover 500 people waiting for them, some for over two hours, but what really caused all the problems was a government ban on over-time which forced the MVB staff to ensure that they closed on-time at 6:00 p.m. - thus locking the doors at 5:30 p.m. To defuse the situation, the police swapped tear-gas for a friendly announcement; motorists caught with expired plates on March 1st would only be given a warning, but tickets would be given out starting March 2nd. |

With the run now complete (as of 2015), the focus is switching to having as many of the plates be from 1967 as possible. Postscript: sadly, our friend Tom passed in 2020 and the “Lindner 100” has joined the “Garrison 100” and moved into other collector's hands for safe keeping. |

* * * * * |

| 1968 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Registration numbers continued to climb, surpassing three-quarters of a million plates for the first time, while the usual calls for permanent and reflectorized plates occurred throughout the year. Otherwise, 1968 was a very quiet year. |

| Gallery |

* * * * * |

| 1969 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

It would also be the last year that new plates would be issued annually, as the 1970 plates were to be “permanent” (at least for 3 years) and renewed by decals (see 1970-1978). |

| Gallery |

| This is one way to put excess BC plates from the 1950s through to the 1970s to good use. I would think these plates added decades to the life of this shed. |  |

Quick Links: |

Antique | APEC | BC Parks | Chauffeur Badges | Collector | Commercial Truck | Consul | Dealer | Decals | Driver's Licences | Farm | Ham Radio | Industrial Vehicle | Keytags | Lieutenant Governor | Logging | Manufacturer | Medical Doctor | Memorial Cross | Motive Fuel | Motor Carrier | Motorcycle | Movie Props | Municipal | National Defence | Off-Road Vehicle | Olympics | Passenger | Personalized | Prorated | Prototype | Public Works | Reciprocity | Repairer | Restricted | Sample | Special Agreement | Temporary Permits | Trailer | Transporter | Veteran | Miscellaneous |

© Copyright Christopher John

Garrish. All rights reserved.

It was reported that the decision to use the “Beautiful” slogan was “prompted by [the] growing popularity of [the] provincial government's quarterly brochure “Beautiful British Columbia””, which had begun publication in 1959 and would play a major role in the development of the province's tourism industry throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

It was reported that the decision to use the “Beautiful” slogan was “prompted by [the] growing popularity of [the] provincial government's quarterly brochure “Beautiful British Columbia””, which had begun publication in 1959 and would play a major role in the development of the province's tourism industry throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In August of 1963, the province confirmed that the colour of the 1964 plates would be the reverse of the 1963 plates, so blue numbers and letters on a white background and

In August of 1963, the province confirmed that the colour of the 1964 plates would be the reverse of the 1963 plates, so blue numbers and letters on a white background and  but less than 600,000 (573,750 to be precise) of these would be for use on cars and that prisoners at Oakalla had already begun to work on the new plates (as of August 1963).

but less than 600,000 (573,750 to be precise) of these would be for use on cars and that prisoners at Oakalla had already begun to work on the new plates (as of August 1963).

Not surprisingly, given its 1962 Editorial (see above), the first to make hay out of the new slogan was the Vancouver Province newspaper and its columnist Eric Nicol, who, in mid-January of 1964, proclaimed it “plug ugly” (meaning extremely unattractive, or the opposite of “Beautiful”);

Not surprisingly, given its 1962 Editorial (see above), the first to make hay out of the new slogan was the Vancouver Province newspaper and its columnist Eric Nicol, who, in mid-January of 1964, proclaimed it “plug ugly” (meaning extremely unattractive, or the opposite of “Beautiful”); Two weeks later, the Province along with the Victoria Daily Times picked up the story of Kenneth Froslid, a New York motorist who was protesting the inclusion of a reference to the World's Fair that year in New York City by covering up the slogan and demanding a new pair of plates without the slogan.

Two weeks later, the Province along with the Victoria Daily Times picked up the story of Kenneth Froslid, a New York motorist who was protesting the inclusion of a reference to the World's Fair that year in New York City by covering up the slogan and demanding a new pair of plates without the slogan.

This prompted a response the following day from the Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB), George Lindsay, who “warned that it is a punishable offence under the Motor Vehicle Act to mutilate licence plates, or to cover them up.” Lindsay also reassured motorists that “our plates do nothing more than express the truth.”

This prompted a response the following day from the Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB), George Lindsay, who “warned that it is a punishable offence under the Motor Vehicle Act to mutilate licence plates, or to cover them up.” Lindsay also reassured motorists that “our plates do nothing more than express the truth.”  Even the Attorney-General, Robert Bonner, waded into the debate to clarify that “the problem in New York arises from the fact that the world's fair is a private venture supported by public bond issue and is not in my understanding an accredited world fair as were the Brussels or Seattle ones with official status. Beautiful describes the province and does not advertise any private venture in our midst. Other provinces and states - more than half those on the continent - engage in B.C.'s new practice.”

Even the Attorney-General, Robert Bonner, waded into the debate to clarify that “the problem in New York arises from the fact that the world's fair is a private venture supported by public bond issue and is not in my understanding an accredited world fair as were the Brussels or Seattle ones with official status. Beautiful describes the province and does not advertise any private venture in our midst. Other provinces and states - more than half those on the continent - engage in B.C.'s new practice.” Lindsay stated that “disgruntled motorists who obscure the word 'beautiful' from their licence plates could be prosecuted” and that CONNED AGAIN “couldn't have seen the province because it is a beautiful province.”

Lindsay stated that “disgruntled motorists who obscure the word 'beautiful' from their licence plates could be prosecuted” and that CONNED AGAIN “couldn't have seen the province because it is a beautiful province.” A few more Letters to the Editor from motorists on both side of the issue followed, including one from “G.W.” in North Vancouver felt it would be a “pity to let the issue drop” as the slogan was unrelated to the purpose of a licence plate and he should not have to display it.

A few more Letters to the Editor from motorists on both side of the issue followed, including one from “G.W.” in North Vancouver felt it would be a “pity to let the issue drop” as the slogan was unrelated to the purpose of a licence plate and he should not have to display it.

60 years later, the “Beautiful” slogan remains the

oldest license plate slogan in use amongst the Canadian provinces, while its introduction also marked the last time that Harry Duker (shown at left in 1968) came forward publicly to advocate for his beloved “Totemland” slogan.

60 years later, the “Beautiful” slogan remains the

oldest license plate slogan in use amongst the Canadian provinces, while its introduction also marked the last time that Harry Duker (shown at left in 1968) came forward publicly to advocate for his beloved “Totemland” slogan. When Duker died in March of 1982, his family held his funeral service at the Simmons and McBride Funeral Home (Mount Pleasant).

When Duker died in March of 1982, his family held his funeral service at the Simmons and McBride Funeral Home (Mount Pleasant).  With the slogan and colour issues now set for the remainder of the decade, there was little to report at the beginning of each year.

With the slogan and colour issues now set for the remainder of the decade, there was little to report at the beginning of each year.  1965 was, however, the first year that plate No. 600-000 would be issued (a new high), there was renewed chatter over the merits of permanent and reflective plates, while a minor change at the Motor Vehicle Branch was implemented to encourage people to pick-up their plates in-person as opposed to mailing in requests.

1965 was, however, the first year that plate No. 600-000 would be issued (a new high), there was renewed chatter over the merits of permanent and reflective plates, while a minor change at the Motor Vehicle Branch was implemented to encourage people to pick-up their plates in-person as opposed to mailing in requests.

The Victoria Times decided to ask locals, including the operator or a parking lot who reported that “we don't see many of those around. There are a few, but not many”, a random motorist who claimed “I don't remember getting one” and Laurie Wallace, Chair of the Centennial Committee, who reassured readers that there was “a much higher percentage on cars in the interior and on the mainland.”

The Victoria Times decided to ask locals, including the operator or a parking lot who reported that “we don't see many of those around. There are a few, but not many”, a random motorist who claimed “I don't remember getting one” and Laurie Wallace, Chair of the Centennial Committee, who reassured readers that there was “a much higher percentage on cars in the interior and on the mainland.” On November 25, 1966, the 54th Grey Cup between the Saskatchewan Roughriders and the Ottawa Rough Riders (yes, they had basically the same name back then) was held at Empire Stadium in Vancouver.

On November 25, 1966, the 54th Grey Cup between the Saskatchewan Roughriders and the Ottawa Rough Riders (yes, they had basically the same name back then) was held at Empire Stadium in Vancouver.

Of interest, one of the participants in the Parade was the Commissioner of the Northwest Territories (NWT), Bent Sivertz (shown at right), who brought with him the pair of No. 1 NWT license plates for 1966 to use on his car.

Of interest, one of the participants in the Parade was the Commissioner of the Northwest Territories (NWT), Bent Sivertz (shown at right), who brought with him the pair of No. 1 NWT license plates for 1966 to use on his car.

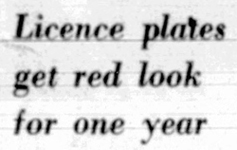

British

Columbia’s contribution, however, be much subtler.

No special slogans were adopted, nor was any reference made

to 1867 as Alberta, Ontario and Quebec had done. Instead,

BC dropped its blue-and-white colour policy for one year in order to issue plates in the national colours

of red-on-white.

British

Columbia’s contribution, however, be much subtler.

No special slogans were adopted, nor was any reference made

to 1867 as Alberta, Ontario and Quebec had done. Instead,

BC dropped its blue-and-white colour policy for one year in order to issue plates in the national colours

of red-on-white.

Given the significance of the Centennial, competition for the license plates bearing the numbers “1867” or “1967” was going to be intense.

Given the significance of the Centennial, competition for the license plates bearing the numbers “1867” or “1967” was going to be intense.

If you are like us, you're excused for thinking the headline at right was published in relation to a convention of license plate collectors gone-sideways, but it actually relates to one of the most screwy near-riots in BC history!

If you are like us, you're excused for thinking the headline at right was published in relation to a convention of license plate collectors gone-sideways, but it actually relates to one of the most screwy near-riots in BC history!

.jpg)

15 years in the making the

15 years in the making the  Returning to the policy of rotating blue-and-white colour schemes after the red Canadian Centennial plates, the 1968 license plates picked up as if the red used on the 1967 never happened and displayed the same blue-on-white colours as the 1966 plates.

Returning to the policy of rotating blue-and-white colour schemes after the red Canadian Centennial plates, the 1968 license plates picked up as if the red used on the 1967 never happened and displayed the same blue-on-white colours as the 1966 plates.

Displaying the reverse blue-and-white colour scheme of the 1968 plates, the 1969 plates incorporated the exact same layout, however, this would be the last year that an all-numeric serial would be used as the total number of car plates made exceed 800,000 for the first time.

Displaying the reverse blue-and-white colour scheme of the 1968 plates, the 1969 plates incorporated the exact same layout, however, this would be the last year that an all-numeric serial would be used as the total number of car plates made exceed 800,000 for the first time.

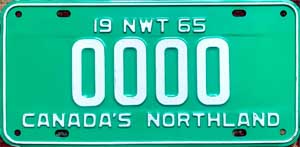

In 1957, the Plate Shop at Oakalla began producing license plates for the Yukon Territory. As a result, correspondence between the Territory and the Plate Shop has survived and presents an interesting insight into the manufacturing of license plates at a public facility staffed by prison labour in the mid-1960s.

In 1957, the Plate Shop at Oakalla began producing license plates for the Yukon Territory. As a result, correspondence between the Territory and the Plate Shop has survived and presents an interesting insight into the manufacturing of license plates at a public facility staffed by prison labour in the mid-1960s.

In early 1966, Oakalla wrote the Yukon Government advising that, “on the assumption that you will be submitting your purchase order for the manufacture of your 1967 Licence Plates, we have purchased sufficient metal to cover your order ... and would appreciate some assurance from you that you will be favouring us with your order.”

In early 1966, Oakalla wrote the Yukon Government advising that, “on the assumption that you will be submitting your purchase order for the manufacture of your 1967 Licence Plates, we have purchased sufficient metal to cover your order ... and would appreciate some assurance from you that you will be favouring us with your order.”