|

British

Columbia Passenger License Plates

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quick Links: |

The period between 1931 and 1976 is considered to be the "Prison Era" when BC plates were manufactured by inmates at Oakalla Prison in Burnaby. |

* * * * * |

Despite the myriad of problems with the metal renewal tabs that the province had experimented with in the early 1950s and their early abandonment, the idea of a “permanent” license plate never receded from the public consciousness:

In the years after 1954, various “cri de couer” from motorists with skinned and frozen knuckles from wrestling with their license plates each winter at renewal time would appear in the Letter to the Editor pages of the various major newspapers. Invariably, these appeals would cite the following jurisdictions with “permanent” plates and ask why British Columbia could not do something similar:

|

Missouri had pioneered the use of plastic registration decals in 1954, while California followed suit a few years later. Observant motorists soon began to ask;

By the early 1960s, the Editorial pages of the major newspapers re-joined this chorus, noting that Manitoba's “system appears so satisfactory to the prairie province, and the anodyzed aluminum plates have lasted so long, that there is reason to wonder why British Columbia does not similarly forgo its annual licence-changing.”

In the mid-1960s, Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) began to raise the issue, with Alex MacDonald, Vancouver East (NDP), in 1964 and Dudley Little, Skeena (Social Credit) in 1965 both endorsing the idea.

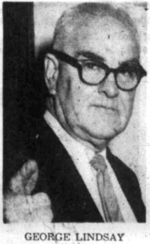

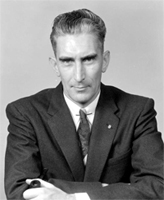

Freed from the institutional constraints of the MVB, Lindsay went rogue on the first day of his retirement by speaking to the press in favour of what must have been a hobby-horse he was pursuing in his last years; a switch to a “permanent” plate with annual license fees replaced by a surcharge on gasoline sales. |

|

|

Lindsay suggested that studies had already been conducted by the Branch to determine the feasibility of such a system with the idea being that heavier users of the road system pay more (i.e. gas guzzling heavy vehicles, or people who drive many miles a year) than lighter users of the road system. He further hinted that the savings could be in the millions of dollars. This clearly displeased his former co-workers in the Attorney-General's office as it was leaked to the press the following week that Lindsey's idea had not passed muster with the economists in the office, who had found that it would require a 5-cent increase to the existing 13-cent provincial Gas Tax. Such an increase would likely impact the tourist industry and also prompt “bootlegging” of gas at the Alberta and US border points. While nothing would come of Lindsey's idea, important institutional voices continued to advocate for a “permanent” license plate, such as the BCAA, who presented its idea to the provincial Cabinet that five-year aluminum plates with renewable tabs for each would result in significant savings. The Vancouver Province and Vancouver Sun newspapers also continued to print Editorials promoting the idea, including this entry from the Sun in 1966:

So, when the province announced on March 1, 1969, that it would be introducing a “permanent” license plate for 1970, the news was somewhat anti-climactic. The Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and PEI had already been using decals as were many US states and their introduction to BC was no longer a question of “if”, but “when”.

The main reason for the change was increasing costs, but the province had already announced in 1966 that it was exploring the introduction of letters (see below) as vehicle registrations were forecast to surpass 999,999 by the 1970 and the available space on the current license plates.

|

| 1970-72 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

With vehicle registrations quickly nearing the 1,000,000 mark and the total number of combinations on a 6-digit numerical plates (e.g. 999,999 available combinations), the MVB was going to re-consider the use of letters.

Hadfield expressed doubts that such a system of lettering could accurately identify the origins of a vehicle as many license plates were issued by mail and approximately 20% of motorists changed their address each year. As an example, Hadfield cited a car originally registered in Prince George whose owner relocated to Vancouver. The PG lettered plates would remain on the car. Instead, the MVB was hoping that “a comprehensive international study” that was then underway would determine “which of the letter prefix systems are best” for identifying a license plate. Also, a new computer system would be required to assist with administration of such a licensing system and to avoid the problems that had beset the letter-number combinations used on the Totem base between 1952-54. Hadfield hinted that another challenge posed by the use of letters was going to be the occurrence of potentially “distasteful” combinations of letters! In the end, the Minister and Superintendent both got their ways. Hadfield was able to introduce the common AAA-000 format used by multiple jurisdictions, including Washington and California (whom British Columbia looked to regularly for license plate inspiration), while Kiernan got prefixes assigned to specific towns and regions:

While a more detailed breakdown by region and town is provided below, the allotment of the first letter by region is summarized as follows:

|

| Gallery - Vancouver Island | ||||

BDA-001 to BDK-999 (Courtenay) |

BFA-001 to BFK-999 (Nanaimo) |

|||

| Gallery - Central & Northern BC | ||||

| Gallery - Lower Mainland | ||||

FJA-001 to FKK-999 (North Vancouver) |

||||

| Gallery - Okanagan & Kootenay's | ||||

|

||||

Well, we here at BCpl8s.ca have been told two stories. One is that the stamps used by employees of the MVB for compiling licensing documents in 1960s only had enough space for ten (10) characters. The other is that when the province upgraded the machinery at the Oakalla Plate Shop in the mid-1950s, it was designed to accommodate a maximum row of ten (10) different dies for each of the six columns that might be used in the license plate's serial. Regardless of which, if any of these stories is the correct one, the alphabet was broken into two blocks of ten letters with the first block comprising A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, and K with “I” excluded as it too closely resembled the number one:

As result, once plate AAK-999 had been issued the next plate in the series was ABA-001 as opposed to AAL-001, despite AAL-001 being the next sequential combination. For the second half of the alphabet, which would be used in the second and third columns of the serial on a short over-run series in 1972, the ten letters would be L, M, N, P, R, S, T, V, W, and X with “O”, “Q”, “U”, “Y” and “Z” being excluded. Clear as mud, right? |

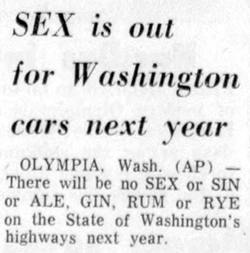

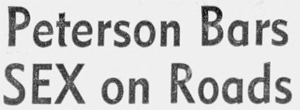

Although Washington had switched to a AAA-000 format in 1958, and used this same format again when new plates were issued in 1963, the BC press had not taken much interest. This change in 1968, when all four of the major newspapers reported on the letter combinations Washington was excluding from its new license plates, including those denoting sex and alcohol (see at right), but also BAT, APE, DOG, FOX, PIG, RAT, YAK, COW, MOO, FBI, SPY, DAD AND POT. The Director of the State Department, Doug Toms, explained their rationale as not wanting a person's license plate to be a source embarrassment or to be grounds for a motorist to refuse a license plate due the letters being in bad taste.

In addition to RYE, GIN, RUM, ALE, PIG, RAT, COW, SEX, SIN, MOO, CIA, FBI, SPY, COP, FAG and HAG (all seen on Washington's list) was added some distinctly Canadian / British combinations such as CAD (i.e. a man who behaves dishonourably, especially towards a woman). Peterson acknowledged that the MVB had been in touch with its counterparts in other provinces and US states to find out which combinations they had excluded. Some motorists saw the irony of this decision coming from a government that had been in power for 18 years and had suffered its fair share of scandals and controversies, yet was trying to impose moral standards on license plates. Others accused the government of being a buzz-kill and not trusting its citizens to contain their emotions upon seeing a random collection of letters on a license plate that might spell something objectionable. While some excluded letter combinations elicited nothing but bafflement:

Naturally, this provided another opportunity to gain an insight into what generally tickled the fancy of male headline writers ... |

For the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB), the switch to a new AAA-000 format had a potentially significant side-benefit; the end of the Reserve List! The Reserve List was an expensive and burdensome program administered by the Branch, and without cost to motorists since the 1920s in which low numbers were held back and re-issued to motorists upon request. If a motorist did not renew a number from the Reserve List, it was assigned to the next person who had asked for it.

It was due to the Reserve List that collections of plates with the same number (usually under 3,000), assembled over multiple years still exist to this day (such as the No. 1773 run shown at right). So, when the province announced the ending of all-numeric plates, it was not lost on the public that this might spell the end of the Reserve List, or “Snob” plates as one reporter termed it. Aware, however, that motorists might try to perpetuate the practice by requesting initials or other coveted letter combinations (such as “AAA”), the Superintendent, Ray Hadfield, made it known that such requests would be ignored.

Whereas most everyone else in the province waited to the last minute to get their new plates from the MVB, Victorians had a long history of lining up at the Branch's main office on Menzies Street the first day that a new year's license plate were issued in the hopes of getting a newly available number from the Reserve List.

So, naturally, on the night of January 4, 1970, a line-up began to form at midnight in front of the Menzies Street office and was comprised of motorists seeking to get a trophy in the form of a new low numbered plate.

When the MVB opened the Menzies Street office at 8:30am and Rogers presented himself at the first wicket, he was handed plate number “AAA-003”! Rogers knew the AAA-001 and AAA-002 plates were in the office as an MVB employee had held the plates up to the office window for those waiting in line outside to see, and this was just before the office opened at 8:30am.

After being told the AAA-001 and AAA-002 had been legally issued and Rogers would have to settle for -003 and -004, a formal complaint was lodged with the MVB as it has previously advised that the Reserve List was dead and plates would be issued on a “first come, first served” basis.

At first, the Branch obfuscated, insisting that the AAA-001 and AAA-002 plates could have only been issued in the normal way and that the complaint was likely unfounded.

Jackson announced that “I'm fed up with this whole thing”; the “thing” being the seemingly endless coverage that the local Victoria radio stations and newspapers were devoting to the missing plates.

While Jackson was being purposely vague in his response - keeping in mind it was the MVB's primary job to ensure it knew who a particular plate was registered to - he also tried to deflect any blame by introducing a little after-the-fact revisionism. Apparently, according to Jackson, Branch employees “weren't supposed to get the low numbers and this was our main concern” [emphasis added]. This, however, ran contrary to the Branch's earlier stated “main concern” of ending the Reserve List and only issuing plates on a “first come, first served” basis. Speculation over the fate of the missing plates became absurd (but all in good fun) when they were linked to a UFO sighting that had occurred at the Duncan hospital the same day Rogers had been issued the AAA-003 plate:

In the absence of a better explanation, why couldn't the AAA-001 and AAA-002 plates be flying around the Milky Way attached to the bumpers of flying saucers piloted by a “Human-Like Pair”!?!? A hint of what actually happened, however, can be found in how the Branch responded to previous rushes for new license plates.

This was known to be a common MVB practice in the busier urban centres of the province each January, including in Victoria. Two weeks later, on January 21, 1970, the mystery was solved. Local media tracked down, through MVB records (surprise! surprise!), that AAA-001 had been issued to John J. Smith while the AAA-002 plate had been issued to Andrew L. Mack, both of Victoria and both of whom had been called in to temporarily help with the first-day rush at the Menzies Street office.

The media went so far as to phone Smith at work, and were diverted to the HR department, who advised that “all we can say is he is a permanent employee of the board and employed in Victoria.” They also tried to reach Mack at home, but were told he could not come to the phone. It was many more weeks before the cars with AAA-001 and AAA-002 were seen regularly around Victoria after having spent most of January hidden away in garages. |

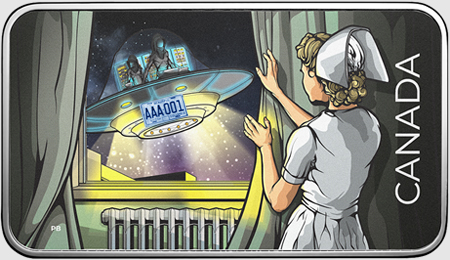

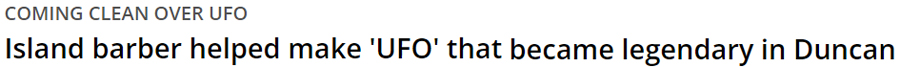

Although it took much longer, the UFO mystery was eventually solved as well. As part of its “Unexplained Phenomena Series”, the Royal Canadian Mint produced a pure silver Glow-in-the-Dark coin to commemorate “The Duncan Incident” in November of 2023 (which we have embellished ... slightly):

The Mint described “The Duncan Incident” as follows:

|

|

In the late 1960s, White and a friend used plastic sheets salvaged from lumberyards, ironed them together to create a balloon shape and then added a frame to the bottom to hold a pie plate that they filled with a gelled denatured alcohol called Sterno to heat the balloon and lift it skyward. According to White, “the heat would fill the balloon and give it an unworldly glow ...” and, for New Year's Eve 1970, it was decided to bring one to a party in Duncan they had been invited to. The balloon was launched from the Hospital's parking lot “because there was a wind that night, and [we] used the hospital as a shield from the wind.”

With the coin from the Canadian Mint coming out, White felt it was time for the truth to come out. |

In early February of 1970, the Vancouver Province newspaper ran a short column marveling at the resourcefulness of motorists who, despite the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) not reserving letter combinations, “have discovered a way to pick and choose” the letters they want. Noting that “there's no law against you finding out however you can what areas are selling plates with certain letters”, the Province profiled the case of plate number “HBC-300”, which was being driven around by D.G. “Pete” Buckley, Regional General Manager of the Hudson's Bay Company. As reported by the Province, “company sleuths discovered that the Richmond office was selling plates with HBC prefixes, and The Bay sent scores of applications for plates to that office. Some enterprising Bay employee ensured that Buckley's car got the coveted 300 number - he'll go places.”

Apparently, “at least one other company [was] running around in tight circles trying to find the office that deals in its initials, so far to no avail.” What company this might have been was not stated by the Province. Seemingly unbeknownst to the Province, its rival, the Vancouver Sun, had published a summary of the letter combinations available at local MVB offices two weeks earlier, including the following entry:

Richmond in the early 1970s had a population of around 50,000 to 60,000 and likely only had one MVB office, so tracking down the “HBC” prefix really would have been “easy”! |

|

A less obvious error (if that is, indeed, what it is) can be seen on this plate which displays one of the letters from the second half of the alphabet ("P") as the first character in the serial. |

|

|

Mistakes were bound to occur in the transition to the new AAA-000 format, and a notable one involved the production of 1,000 sets of the plates (or 2,000 individual plates) that ended with “000”. Since the mid-1920s, the province had issued “Sample” license plates to other jurisdictions for identification purposes and also to collectors which always displayed the same number; all zeros. To ensure these plates weren't passed off as legitimate, the law stipulated that zero, or any number of zeros was not considered a number. Consequently, Stu Jackson, Deputy Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) conceded it was not known how this mistake had occurred and that the plates could not be sold and would probably be stored by the MVB. In the end, they were generally distributed to collectors as “Sample” license plates between 1970 and 1972, which is why actual “Sample” license plates from this period are so hard to come by. |

It seems that, in the early 1970s, a lot of British Columbia motorists had a tow hitch on the back of their cars and that the design of cars had the location of the license plate in a spot where the “ball” of the hitch obscured the new decals, as shown:

Testing station officials in Vancouver began to warn-motorists that this situation couldn't go on; “If there's nothing else wrong with the car we just give them a warning but if there are other defects we are telling them to get the ball taken off.” This was not an issue in 1970 as the decals being provided to motorists were decorative in nature and only intended to serve as practice for forthcoming years. The Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) crunched some numbers and estimated that approximately 100,000 vehicles could be affected by this “hitch” and began to advise affected motorists to take their balls off and only use them when needed (i.e. the weekend). Unfortunately, with the majority of the 1970-72 plates having already been manufactured at Oakalla, the soonest that a fix, in the form of a relocated decal box could occur would be with the new plate series planned for 1973. |

It is generally understood that these were souvenir plates that were sold at the Canadian Pavilion at the 1970 World's Fair (Expo 70) held in Tokyo, Japan. That said, this has not yet been definitively confirmed. |

By October of 1971, the initial series of 1,000,000 passenger license plates had been issued and the MVB was required to order an additional 100,000 plates.

These over-run plates picked up where the original series left off by continuing to use a “K” prefix followed by letters between “L” and “X” (but excluding “O”, “Q”, “U”, “Y” and “Z”), or from KLL-001 to KXX-999 and would be issued starting in 1972. Of interest for collectors is the intermittent use of a dash separator between the characters and digits, which would also characterize the 1973 license plate series as well: |

| Gallery - KLL to KXX series | ||||

"KL-" |

"KM-" |

|

||

"KS-" |

"KV-" |

|

||

Quick Links: |

|

© Copyright Christopher John

Garrish. All rights reserved.

Tongue-in-cheek, the Victoria Colonist newspaper suggested that there might be a significant drawback preventing the introduction of “permanent” plates:

Tongue-in-cheek, the Victoria Colonist newspaper suggested that there might be a significant drawback preventing the introduction of “permanent” plates:  Even the Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB), George Lindsey, came out in support of “permanent” plates on the occasion of his retirement in January of 1965 - despite his office having provided a detailed explanation of why such plates were not economically feasible only three years earlier.

Even the Superintendent of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB), George Lindsey, came out in support of “permanent” plates on the occasion of his retirement in January of 1965 - despite his office having provided a detailed explanation of why such plates were not economically feasible only three years earlier.  Even delegates to the annual convention of the ruling Social Credit Party had begun to pass resolutions calling on the government to move on “permanent” license plate.

Even delegates to the annual convention of the ruling Social Credit Party had begun to pass resolutions calling on the government to move on “permanent” license plate. In making the announcement, Attorney-General Lesley Peterson stated that these “permanent” plates were intended to last between two or three years and, after this initial trial period, “there will be a move into five-year or permanent plates” in order to “get away from the annual long lines such as we are having today.”

In making the announcement, Attorney-General Lesley Peterson stated that these “permanent” plates were intended to last between two or three years and, after this initial trial period, “there will be a move into five-year or permanent plates” in order to “get away from the annual long lines such as we are having today.”

The other problem that had doomed the last attempt at a

The other problem that had doomed the last attempt at a

The Branch's hand was forced in November of 1966 when Superintendent Ray Hadfield had to confirm that the Branch was, indeed, exploring the use of letters on passenger vehicles after Ken Kiernan, Minister of Recreation and Conservation, let slip to a meeting of the Provincial Tourist Advisory Council that

The Branch's hand was forced in November of 1966 when Superintendent Ray Hadfield had to confirm that the Branch was, indeed, exploring the use of letters on passenger vehicles after Ken Kiernan, Minister of Recreation and Conservation, let slip to a meeting of the Provincial Tourist Advisory Council that

So, why did BC only use letters between A and K on the first million 1970 license plates?

So, why did BC only use letters between A and K on the first million 1970 license plates?

After the MVB Superintendent, Ray Hadfield, had expressed his concerns about the

After the MVB Superintendent, Ray Hadfield, had expressed his concerns about the  Not surprisingly, when Attorney-General Leslie Peterson announced the letter combinations BC would be excluding from its 1970 license plates in August of 1969, the list was almost identical to Washington's, and why not given the cultural similarities between the two jurisdictions.

Not surprisingly, when Attorney-General Leslie Peterson announced the letter combinations BC would be excluding from its 1970 license plates in August of 1969, the list was almost identical to Washington's, and why not given the cultural similarities between the two jurisdictions.

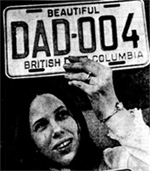

It was reported that one of the only letter combinations that spelled an actual word that was allowed to be issued was “DAD”. All other letter combinations that spelled words had been weeded out by the MVB in order to try and avoid any complaints or embarrassment.

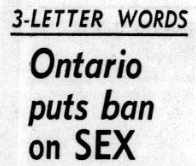

It was reported that one of the only letter combinations that spelled an actual word that was allowed to be issued was “DAD”. All other letter combinations that spelled words had been weeded out by the MVB in order to try and avoid any complaints or embarrassment. As an aside, when Ontario announced it was introducing the AAA-000 format for use on its license plates three years later (i.e. 1973), it relied on the same lists as British Columbia for undesirable word combinations.

As an aside, when Ontario announced it was introducing the AAA-000 format for use on its license plates three years later (i.e. 1973), it relied on the same lists as British Columbia for undesirable word combinations. Despite the paternalism and protestations, the inevitable happened to Vancouver radio DJ John Tanner, who was working the 9 pm. to midnight shift at CKLG AM 730 when the new plates came out.

Despite the paternalism and protestations, the inevitable happened to Vancouver radio DJ John Tanner, who was working the 9 pm. to midnight shift at CKLG AM 730 when the new plates came out. Given the novelty of the letter prefixes, the station decided to run a segment in 1970 entitled “Freaky License Plates” where listeners could phone and report on whatever combination of letters they had seen that day that inadvertently spelled a word.

Given the novelty of the letter prefixes, the station decided to run a segment in 1970 entitled “Freaky License Plates” where listeners could phone and report on whatever combination of letters they had seen that day that inadvertently spelled a word.

The Reserve List was initially for numbers between 1 and 8,000, but this was reduced in subsequent decades to 1 and 5,000 before the Branch settled on numbers 1 to 3,000. By the mid-1960s, the number of motorists waiting for a low number was reported to be over 35,000.

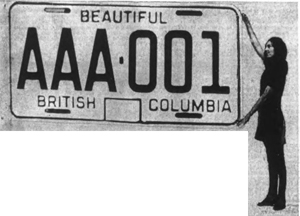

The Reserve List was initially for numbers between 1 and 8,000, but this was reduced in subsequent decades to 1 and 5,000 before the Branch settled on numbers 1 to 3,000. By the mid-1960s, the number of motorists waiting for a low number was reported to be over 35,000. The Branch did not, however, help its cause when it allowed the new plates to be extensively publicized, particularly the first plate in the new series, AAA-001, which received its own photo profile in the Victoria press.

The Branch did not, however, help its cause when it allowed the new plates to be extensively publicized, particularly the first plate in the new series, AAA-001, which received its own photo profile in the Victoria press.

First in line was Bruce Roger (shown at right), whose goal was to get plate numbers “AAA-001” and “AAA-002” for use on his and a family members cars. He was subsequently joined in line by others, including a resident from Vancouver who had made the trip from the Mainland to try and get a low number.

First in line was Bruce Roger (shown at right), whose goal was to get plate numbers “AAA-001” and “AAA-002” for use on his and a family members cars. He was subsequently joined in line by others, including a resident from Vancouver who had made the trip from the Mainland to try and get a low number.

The following day, January, 7, 1970, the Deputy Superintendent of the MVB, Stu Jackson, when to the press to defend the actions of his staff.

The following day, January, 7, 1970, the Deputy Superintendent of the MVB, Stu Jackson, when to the press to defend the actions of his staff. Jackson went on to state that “I think our staff handled this very well, and we now know the plates were issued across the counter”, but he refused to divulge who received them other than to clarify that the motorists were “not an employee of the branch.”

Jackson went on to state that “I think our staff handled this very well, and we now know the plates were issued across the counter”, but he refused to divulge who received them other than to clarify that the motorists were “not an employee of the branch.”

In an article from 1967 (at left), it was reported that the MVB had recruited staff from provincial government liquor stores to assist with the issuance of license plates at its West Georgia Street office in Vancouver.

In an article from 1967 (at left), it was reported that the MVB had recruited staff from provincial government liquor stores to assist with the issuance of license plates at its West Georgia Street office in Vancouver. Smith was confirmed to be a clerk with the Liquor Control Board while Mack was a member of the Canadian Armed Forces.

Smith was confirmed to be a clerk with the Liquor Control Board while Mack was a member of the Canadian Armed Forces.

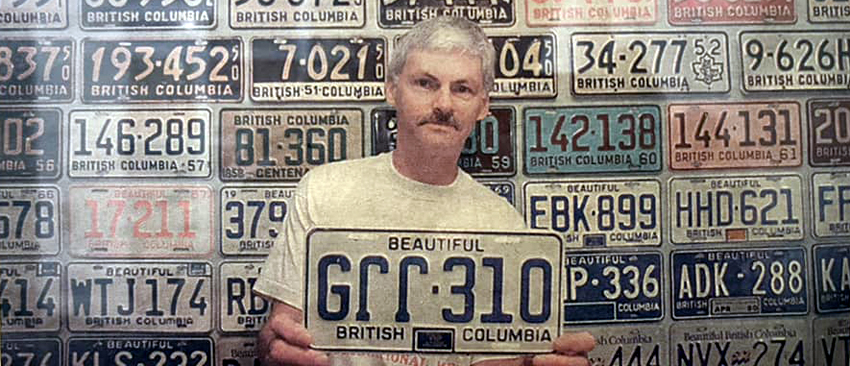

With the Mint's announcement of the new coin, Jan White, of Esquimalt, decided it was time to come clean.

With the Mint's announcement of the new coin, Jan White, of Esquimalt, decided it was time to come clean.  The Bay, of course, was founded on May 2, 1670 in London, England, and 1970 marked its 300th anniversary - hence the significance of plate “HBC-300”.

The Bay, of course, was founded on May 2, 1670 in London, England, and 1970 marked its 300th anniversary - hence the significance of plate “HBC-300”.

The other

The other

From time to time, license plates produced on the 1970 base and displaying the serial number

From time to time, license plates produced on the 1970 base and displaying the serial number