|

British Columbia Driver's Licences |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oh, listen, brother chauffeurs all, |

Mirvina Irving, “The Chauffeur News,” Victoria Daily Colonist, August 1, 1909, p. 8.

|

Quick Links: |

Driver's Licences | Chauffeur Badge Gallery | Licence Gallery |

Conflict followed the introduction of the automobile, and many jurisdictions across North America found that accidents and mayhem followed in their wake. A Editorial that appeared in the Victoria Daily Colonist in 1909 reminding drivers that: |

|

In a separate incident, the Colonist complained that “the ‘rule of the road’ is very frequently violated in Victoria” and proceeded to report on an encounter between a bicycle and an automobile on Esquimalt Road. Tragedy, in this instance, was only averted when the cyclist was able to turn out of the way at the very instant that the vehicle “whizzed past him not more than a foot or so away”. |

Yet, despite this conflict, in almost every state and province, early automobile laws followed the pattern of targeting vehicles for regulation, as opposed to the operators of the vehicle. |

British Columbia was no different in this regard as the 1904 Motor Vehicles Speed Regulation Act made reference only to the registration of “motor vehicles” and not drivers. |

The first North American jurisdiction to attempt to regulate motorists was the City of Chicago when, in 1903, it passed a bylaw that required drivers to be examined and licenced by a Board of Examiners. This law was subsequently struck down by the Illinois Court of Appeal on the basis that the ability to travel on a public road was considered to be a basic right under the U.S. Constitution and could not be curtailed by government regulation. |

Public perceptions in the U.S. against the unregulated operation of automobiles began to harden in response to the growing number of cases of reckless driving and “the daily tribute of human life [being] paid to the rollicking, wanton greed of a few.” |

In this iconic image, the remains of two vehicles involved in an accident near Granville Street and Connaught Drive in 1914 are seen. Given the apparent width of the road and clear sight lines, it is amazing that such a crash even occurred. The vehicle at right, with the No. 7285 licence plate was registered to W.K. Houston & Company of Victoria (IMAGE SOURCE: City of Vancouver Archives). |

*

* * * * |

The first to be targeted for driver’s licencing where the chauffeurs of wealthy vehicle owners. |

In the late nineteenth century, the principal means of transportation had been the horse, which required constant care and attention in terms of feeding, dieting, blanketing, shoeing and grooming; not to mention the upkeep of the carriages and harnesses they were expected to pull. For many wealthy individuals, they could afford to assign these tasks to a hired “coachmen”, who would also be expected to drive the carriage, coach or cart whenever their employer desired to go somewhere. |

Following the introduction of the automobile, the wealthy attempted to recreate this situation by hiring “chauffeurs”, who they gave responsibility for the care and maintenance of the vehicle and for performing driving duties when required. |

By 1907, more than 200 hundred business leaders in the province had purchased automobiles and many of these men (as they invariably were) had neither the time nor the knowledge to look after their vehicles, and considered mechanical problems on a social outing such as long-distance trip to be a nuisance. |

The chauffeur, therefore, was expected to be both driver and mechanic and to ensure that they carried enough tools and supplies to see them through what would be the inevitable breakdown. |

Since many owners were ignorant of how their automobiles worked, some chauffeurs were able to exploit their authority over the vehicle by taking it out for joyride without permission, or to supplement their wages by hiring out use of the vehicle. To protect themselves, vehicle owners began to lobby for changes to existing motor vehicle legislation so that chauffeurs required licencing and had to conform to certain requirements, such as a minimum age and the display of a numbered badge on their clothes. |

This trend was evident in British Columbia when a new Motor-traffic Regulation Act, was passed by the Legislature in 1911 and stipulated that no chauffeur was to operate a motor vehicle unless they had been properly licenced. Obtaining a licence would henceforward be restricted to individuals over the age of 17 and required the submission of two character references to the Superintendent of Provincial Police (who alone determined the moral rectitude of each applicant to act as a chauffeur). |

| Licencing Chauffeurs - 1911 | ||

1911 |

1912 |

There is some conjecture as to the origins of the badges shown at left as the 1911 Act does not make specific reference to the issuance of a metal "badge" to registered chauffeurs. However, it is known - from available records - that approximately 209 licences were issued in 1911 and that a further 345 licences were issued in 1912 (i.e. by starting at No. 210 and proceeding to No. 554). Both of the badges shown display numbers that would correspond to these years, although it is not known why the Province decided to change styles for 1912. |

Once automakers began to focus on producing lower priced cars that would meet the needs of businessmen, tradesmen, and farmers — none of whom could afford to maintain a mechanic-chauffeur — reliability increased and trips of 100 miles or more per day, without incident, became commonplace. This did not stop the increase in chauffeur numbers in British Columbia, but underscored the changing nature of the profession from mechanics to paid professional (taxi) drivers. |

A 1915 City of Vancouver Taxi Licence |

|

The changing nature of a “chauffeur” is seen in this 1921 photo of drivers from the Terminal City Taxi Company in Vancouver. No longer considered to be mechanics, the “chauffeur” is henceforward a professionally paid driver. The identification badges made mandatory for licenced chauffeurs in 1913 can be seen affixed to the hats worn by a number of the drivers’ hats in this photo. (Image Source: City of Vancouver Archives). |

|

*

* * * * |

||

Following the end of World War I, the number of motor vehicle registered in British Columbia began to increase exponentially from only 15,370 in 1918 to 47,615 by 1924 (a number that would almost double again by 1929). One of the unforeseen consequences to this general growth in vehicle ownership was that the number of bad drivers on the road rose as well. In order to curb the perceived “reckless and dangerous driving” on the streets and highways of the province, motorist organisations such the Automobile Club of British Columbia (forerunner of the BCAA) lobbied the government to introduce legislation requiring that all motorists — and not just chauffeurs — be required to obtain driver’s licence. |

||

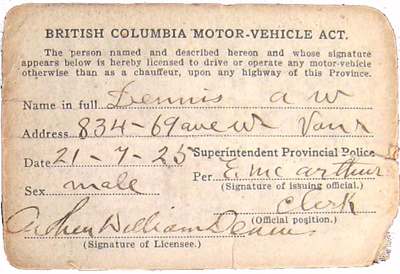

The government obliged in 1924 when it introduced legislative amendments to require all motorists to obtain a driver’s licence from the Superintendent of Provincial Police the following year. |

||

|

||

Good for the life of the person to whom it was issued, these first driver’s licences came at a cost of one dollar which raised the hackles of many a motorist who complained that this was nothing more than a “scheme to get some more dollars” as anyone could obtain a licence without being examined for competency. |

||

In explaining the new system to its members, the Automobile Club estimated that those who posed a public threat when behind the wheel of their vehicle were “habituals ... with a string of convictions ‘as long as your arm’,” against that other 95% who “not a conviction has ever been entered.” While there was seen to be no need to legislate against the majority, it was in “the interests of all of us who observe the law that these others who menace our safety at every intersection should be curbed by the law. |

||

The Auto Club reasoned that the cost to hold examinations for every driver in the province would have been tremendous, while the delay associated with issuing the licences would likely have extended well into the licence year. Besides, “examination would not, as a matter of fact, deal with most of these drivers anyway, as their recklessness comes from too great a facility in the handling of a car rather than from incompetency. They would pass any test with flying colours – any test that is, except the perpetual test of their willingness to obey the law over a period of months or years.” |

||

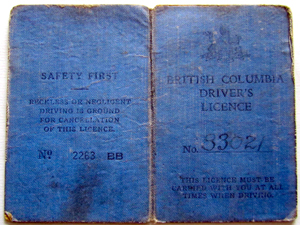

The new licencing system was designed to weed out these individuals as a conviction for a traffic offence would result in the forfeiture of the “white licence card” that had first been issued to them in favour of a “blue licence card”. |

||

|

||

If convicted of another offence while holding a blue card, such individuals stood to be issued a yellow licence. This descending colour scheme was to visually signify if a driver belonged to the supposed 5% of habitual offenders, and would allow the Superintendent of Provincial Police to either suspend or completely cancel the licence of anyone convicted while holding a yellow licence. In this way, “habitual offenders against the law [would] thus be quickly weeded out without any examination”. |

||

Within the first year of operation, however, convicted drivers had already found that they could circumvent the system by requesting a Duplicate Driver’s Licence as the administrative ability to check on the colour of the “lost” licence was not always possible. After a number of cases in which the holder of a blue licence had been able to obtain a duplicate white licence, Motor Vehicle Branch staff were encouraged to be more diligent. |

*

* * * * |

Within two years of universal driver licencing, the Province extended a requirement for those engaged as car “salesmen” to obtain a separate licence “while driving, operating or supervising” a vehicle displaying demonstration licence plates. For years afterward, the Superintendent of Provincial Police, J.H. McMullin, would routinely lament the lack of compliance amongst “salesmen” and encouraging his field officers to visit their local dealerships to ensure that all “salesmen” were properly licenced. |

At the end of 1931, when the Great Depression of that decade was reaching its nadir, McMullin noted that 729 Dealers demonstration number plates had been issued that year against only 245 “salesmen’s” licences for the same period. His conclusion was that there were a large number of vehicles bearing demonstration licence plates being shown by individuals who were not properly licenced and that his officers needed increase their vigilance in this area. |

*

* * * * |

|

Originally, all British Colonies drove on the left side of the road. This changed in British Columbia at 2:00 a.m. on January 1, 1922, when the province made the switch to the right - making it one of the last jurisdictions in Canada to do so. |

|

Prior to this, the practice had been rather arbitrary, with Vancouver Island motorists generally driving on the left, but in the Okanagan the custom was to drive on the right - but to park on either side of the street. Eighteen months earlier, the government had actually mandated right side driving throughout most of British Columbia, but formally extended this to the Island and a few other holdouts in 1922. |

|

The reasons for the change were numerous. First, their was a desire to ensure consistency across provinces (as Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba were already driving on the right - in left-hand drive vehicles) as well as with the States south of the border, an increasing number of motorists from which were now traveling into BC on the rapidly expanding highway networks. |

|

Due to the disruptions associated with the First World War, it was also becoming increasingly difficult to import right-hand drive vehicles from Europe (due to shortages), and with the American automobile industry on the ascendancy, a switch to left-hand drive vehicles only made sense. |

|

While there was concern about how the changeover would go and amount of chaos that might ensue, the transition was actually quite uneventful. Bill Higginbottom, an original bus driver with the BC Electric Company (of a 1918 4-cylinder Blue Funnel 30 passenger bus) recalled many years later that "the biggest problem encountered was with the dray and delivery horses, that insisted on moving without being driven and would end up on the side of the street they were accustomed to travel on." |

|

*

* * * * |

| George Hood - First Superintendent of Motor Vehicles (1945-52) |

To his fellow staff, George Hood, was a revered figure who served the Motor Vehicle Branch admirably and with uncommon “foresight” for four decades. Hood’s career with the Branch started in 1911 when the Superintendent of Provincial Police, Colin Campbell, wanted someone who could implement administrative systems better able to cope with the rapid increase in motor vehicle registrations occurring at that time. |

According to Cecil Clark, who would work alongside Hood after 1916, the “man ate, slept and dreamt motor licencing.” One day, Hood’s superior at the Branch, Charles Booth, went out for lunch and never returned. It was later discovered that Booth had hanged himself in the basement of a vacant house (possibly the John Irving mansion on Menzies Street in Victoria). |

Hood replaced Booth, and his eventual successor George Lindsey recalled decades later, “a better job of [running the Branch] could not have been done by anyone ... We still use most of the ideas and systems instituted by Inspector Hood years ago when there was only a small fraction of today’s volume, and it still stands up. We are very proud of our licensing bureau ... [as] it is considered one of the very best on the North American continent.” |

One of the more innovative practices implemented by Hood was the idea of examining drivers for “visual acuity and to see if they weren’t stone deaf”. According Clark, this raised an uproar amongst optometrists who took to writing the Attorney General asking “who does this man think he is, an oculist, or something?” All that Hood used was a machine that comprised a chair that he used to gauge depth perception of the driver, but compared to Ontario, where drivers could simply walk into a gas station and obtain a licence by paying the requisite fee, road safety in British Columbia was miles ahead. |

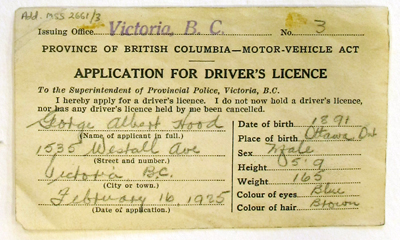

ABOVE: The first Driver’s Licence issued in British Columbia went to prominent Victoria developer Walter Luney on February 16, 1925. Luney’s construction company, Luney Brothers Limited, built many of the City’s historic commercial buildings. Licence No. 2 was in the name of Luney’s wife Florence, while No. 3 (shown above) went to George Hood. (IMAGE SOURCE: BC Archives MS-2661) AT LEFT: “Inspector George Hood tests a motorist for double vision”, circa 1940s ( IMAGE SOURCE: City of Vancouver Archives). |

In 1945, the Provincial Police Commissioner, Tom Parsons, wanted to promote Hood to the rank of Superintendent “to benefit Hood whose great knowledge and participation in the motor vehicle field was so recognisable.” The Attorney General agreed to the creation of the position with the proviso that the Motor Vehicle Branch fall within his Department. Hood would serve as the first Superintendent of the Branch until 1952, and the following is an article he penned in 1926, representing the first written history of BC licence plates: |

*

* * * * |

||

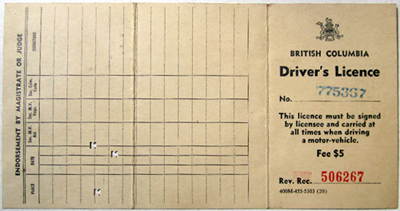

After years of lobbying by local newspapers, the province announced a plan to issue a renewable licence plate for 1951 that would be used for five years. In conjunction with this, it was also decided to introduce a corresponding driver’s licence that would be dated from the person’s birthday and be valid for a period of five years. |

||

|

||

This amendment would spread the work of issuing new licences throughout the whole year and do away with the annual February 28th rush that accompanied the application for licence plates. The cost for a licence would now be $5 (which was the same cost as the $1 annual fee applied over five years), while the minimum fine for operating a vehicle without a driver’s licence was raised from $5 to $25. |

||

|

||

In the Legislature, the opposition Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) objected to the increase in fines as unfair towards the careless driver who forget to bring their licence with them when heading out for a casual drive. The Attorney General, Gordon Wismer, however, defended the move as targeting those who deliberately failed to buy a licence and that such a transgression should be punished severely. |

||

The British Columbia Automobile Association (BCAA) was also not happy about the new licences on the basis that “it isn’t right that any of our people should be forced to buy a license five years in advance”. The Association, whose Directors included various local government politicians, compared the move to the injustice of having to “pay city taxes five years in advance”. However, what the Association seemed to be more peeved about was that the Attorney General had yet to respond to a letter the Association had sent him on May 11th expressing regret that “the motorists of B.C. had not been considered before the plan went into effect.” |

||

Private members in the Legislature opposed to the five-year licence were eventually able to win a minor point during debate of the amendment to the Motor Vehicle Act by making provision for a rebate to be granted on voluntarily surrendered licences. |

|

|

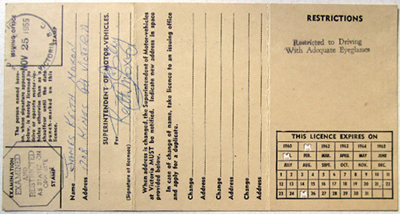

| Although, admittedly, hard to see in the photos shown above, this particular licence was issued on November 25, 1955, but would have expired in five years on the holder’s birthday which, in this instance, was January 25, 1961. This particular driver’s licence was renewed for a second five year term to 1966. | |

|

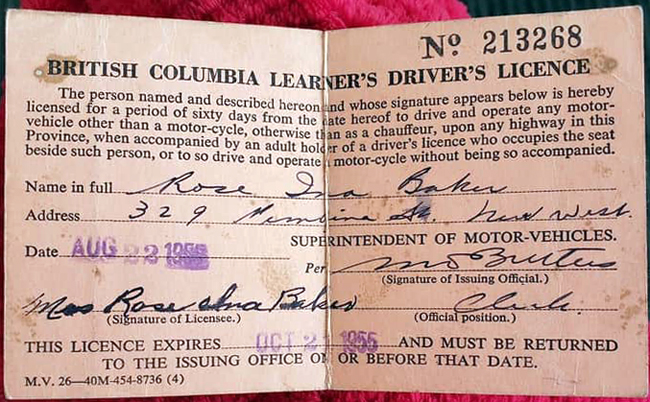

| Shown above is an exceedingly rare Learner's Drivcer's Licence from the 1950s. Valid for a two-month period, the licence was to be returned to the issuing office. Thankfully, this one never was. |

*

* * * * |

In 1971, the Province dispatched the existing licencing system in favour of a new system comprising six (6) different categories in which the licence would reflect the type of vehicle the driver was authosied to operate. The system had been agreed upon by all of the province's in order to bring uniformity to motor vehicle administration across Canada. |

The most common class would be Class 5, which would cover any motor vehicle not exceeding 24,000 pounds gross vehicle weight - or the standard private passenger vehicle or truck. Class 6 was for motorcycles, and both Classes of licences would be issued to motorists without any requirement for additional testing. |

Although Class 'A', 'B' and 'C' Chauffeur licences (and badges) were renewable in 1971 (it is thought that new badges were not issued), after September 1, 1971, these classes of licences would be redistributed into the remaining Classes 1 thru 4. |

*

* * * * |

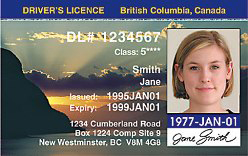

Between August and November of 1996, driver's licence were revamped with a new background (being Shauswap Lake and Bastion Mountain near Salmon Arm in the interior of the province) and a new digital picture identification system that would be transitioned in over the proceeding five years (to 2001). |

|

|

| The image of Shuswap Lake and Bastion Mountain was choosen as it was considered to be a difficult background to duplicate. |

Other security features included a larger picture of the card holder, a tamper-evident date of birth, unobstructed white signature background, holographic image, micro-printing and zigzag lines. |

*

* * * * |

| Facial Recognition & Enhanced Driver's Licences (2009) |

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in New York City, the U.S. government increased security along the Canada border, a trips south of the line became infinitely more difficult and generally not possible without a Canadian Passport. |

To ease some of these restrictions, the Province began working with the Government of Canada and Washington State in 2006 on an Enhanced Driver's Licence (EDL) that would serve as an alternative to the requirement to presenting a Passport when crossing the International Boundary. |

|

|

As part of the background work required to develop the EDL, (then) Solicitor General John van Dongen travelled to Seattle in March of 2007 to meet with (at left) Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff; and (at right) Matt Morrison, Executive Director of the Pacific Northwest Economic Region and Liz Luce, Washington State Director of Licensing as part of a signing ceremony between Washington Governor Christine Gregoire and Chertoof to develop the EDL. NOTE: van Dogen subsequently resigned his position as Solicitor General after it was revealed that he had been issued nine (9) speeding tickets and had his Driver's Licence suspended in 2009. | |

That British Columbia was pioneering work in the area, as the first province in Canada to develop such a licence was not surprising as the Winter Olympic Games were scheduled to occur in Vancouver in February 2010, and it was estimated that there would be significant cross-border visits from Americans coming to see the Games (and that such visits would be aided by Washington's adoption of a similar EDL - the first State in the US to do so). |

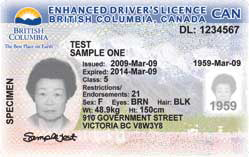

The formal launch of the EDLs occurred on January 21, 2009. Voluntary in nature, the driver's licences issued to participants in the program would be embedded with a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) chip inside the licence - RFID being a wireless technology that retrieves data remotely. |

According to the Provincial Government, the information stored on the RFID chips and provided to border officials comprises: first and last name, birth date, gender, citizenship, licence expiry date, digital photograph, licence status, licence issuing province, RFID unique identifier and tag ID number and a machine readable unique identifier. |

What is not inclued is driving qualifications, driving conviction history, penalties or medical conditions. |

|

|

| Premier Gordon Campbell, along with Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day and Solicitor General John van Dongen unveil a prototype of the new BC EDL in Vancouver on January 21, 2009. | |

A mere two-and-a-half weeks later, on February 6, 2009, Solicitor General, John van Dogen, unveiled a new design for standard driver's licences that now incorporated facial recognition technology. |

Other new features included counterfeit-prevention devices like holographic overlays and laser-engraving and raising of features like the cardholder's image and signature. |

The timing of the new design and security features conincided with similar initiatives being pursued by other provinces and 30 U.S. jurisdictions through the introduction of new licences. The BC licences would be issued to drivers who applied for a new, renewed or replacement card starting March 2, 2009. |

|

|

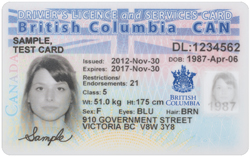

ABOVE: An example of the re-designed, high-tech Driver's Licences introduced in 2009. AT LEFT: |

After another month, the release of the "Enhance" Driver's Licences was announced by the Minister of State for Intergovernmental Relations, Joan McIntyre, on April 6, 2009. |

|

|

ABOVE: An example of the final design of BC's Enhanced Driver's Licence. AT LEFT: B.C. Minister of State for Intergovernmental Relations Joan McIntyre (centre) announced the first phase of the EDL on April 6, 2009, at the downtown Vancouver ICBC driver licensing centre. Joining the minister at the event (left to right): Russ Hiebert, MP, South Surrey-Cloverdale-White Rock; Virginia Greene, Business Council of B.C.; Jim Storie, Council of Tourism Associations; John Yap, MLA, Richmond-Steveston |

*

* * * * |

| Smart Card / Driver's Licences (2013) |

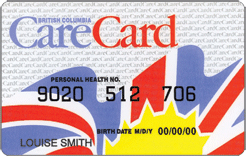

Starting February 15, 2013, driver's licence will be morphing into a new "BC Services Card", which will also double as a CareCard (the provincial health care access card) and it is envisioned that the card will be used to access other government services in future. |

|

|

| An example of the "BC Services Card" is shown at left, while a CareCard (shown at right) was introduced in 1989 and has not been significantly updated over the last 24 years and, much like the current licence plates, continues to bear the "wavey flag" logo so favoured by the Social Credit Party under Premier Bill Bennett in the mid-1980s. | |

The security features remain essentially the same, if not more sophisticated than found in predessor cards, but also now include a chip embedded in the card (as is the fad) that will allow the cards to be read by common card readers. |

Underdstandably, civil rights groups have expressed concern about the morphing of the CareCard and Driver's Licences into a single piece of identification and the ability of government to safeguard citizen's private information. |

We here at BCpl8s.ca wonder if the day will not soon be upon us when all of these "BC Services Cards" will be outfitted with RFID along with our licence plates, thereby allowing law enforcement officials to ascertain if a person driving a vehicle is the lawfully registered owner of the vehicle when they come through road checks? |

Quick Links: |

Driver's Licences | Chauffeur Badge Gallery | Licence Gallery |

Antique | APEC | BC Parks | Chauffeur Badges | Collector | Commercial Truck | Consul | Dealer | Decals | Driver's Licences | Farm | Ham Radio | Industrial Vehicle | Keytags | Lieutenant Governor | Logging | Manufacturer | Medical Doctor | Memorial Cross | Motive Fuel | Motor Carrier | Motorcycle | Movie Props | Municipal | National Defence | Off-Road Vehicle | Olympics | Passenger | Personalized | Prorated | Prototype | Public Works | Reciprocity | Repairer | Restricted | Sample | Special Agreement | Temporary Permits | Trailer | Transporter | Veteran | Miscellaneous |

© Copyright Christopher John

Garrish. All rights reserved.